Everyone was nervous. The players, the caddies, the fans. There was an energy in the air that day, the kind that only a Ryder Cup can produce. Thousands of Team Europe supporters had surrounded the first green, many of them dressed in vibrant costumes and donned war paint on their faces. They wanted to erupt, but for the moment it was quiet.

Everyone’s eyes were locked in on Viktor Hovland.

Ludvig Åberg had flared his approach in Europe’s foursomes match against Max Homa and Brian Harman, and now Hovland was facing the kind of short-game shot that used to cripple him. He was still carrying some mental scar tissue from his first Ryder Cup, at Whistling Straits, when he didn’t chip well and let a partisan American crowd get to him. But this was nightmare fuel. The ball was sitting on the tightest possible lie, practically on the green. If he was going to chip it or pitch it, he’d need to land the ball at the crest of a ridge and use spin to get it close to a tucked right pin.

“We’re all so nervous,” said Homa, who was standing on the other side of the green. “I’m thinking ‘We’re really gonna see this Joe Mayo stuff because he’s chipping from the first cut, and the fringe might as well be the green. It was so awkward. That’s not a golf shot you’d like to hit anywhere, let alone the first hole of the Ryder Cup.”

The safe play would be to putt it, and that’s what Hovland’s caddie, Shay Knight, suggested he do. Hovland shook him off.

“No, I’ve trained for this,” Hovland said. “I can do this.”

The chip came out low and with spin, landing right where Hovland was looking. It trundled up the ridge and then began trickling to the left. With six feet to go, Hovland started walking after it, assuming he needed to study the break for Aberg’s putt coming back. But the ball kept drifting toward the hole. It kissed the pin and dropped into the cup, and the explosion of sound that accompanied Hovland’s fist pump set the tone for the entire Ryder Cup.

“F– yeah!” Hovland shouted over the roar, high-fiving Knight as he strutted after his ball.

Team Europe veterans, who felt protective of Hovland because of the way he was tormented over his short game at Whistling Straits, were beaming.

“He told us later he thought the only way he was going to hole it was to chip it,” said Tommy Fleetwood. “That shows you something. First hole of the Ryder Cup and he’s thinking ‘What’s the best way to hole this?’”

Hovland went 3-1-1 that week and was an essential cog in Europe’s decisive victory. He and Aberg made history on Saturday by beating Scottie Scheffler and Brooks Koepka by the biggest margin (9 & 7) ever in an 18-hole match, and on Sunday, he throttled Colin Morikawa in singles 4&3 to help quash any hint of an American comeback.

It felt like golf’s newest superstar had just grabbed the reins of the sport.

It’s a shame that even the best golf swing is often a fragile, imperfect thing.

Six months have passed since Italy. Hovland is on the far end of the driving range at Augusta National, with two bags of balls near his feet. He looks miserable, even from a distance. Bryson DeChambeau was rolling putts nearby, but after a few minutes, he finished up and left the practice area. Hovland continues to pound balls. Knight, who is at Hovland’s side for every range session, drifts away at one point in search of more tees. Hovland had none left in his bag. Knight returns with a large handful, depositing them near Hovland’s feet.

Every other player in the field is gone.

A small group of fans is watching him from the bleachers. The only sound, besides the hum of leaf blowers, is Hovland’s violent cuts at the ball. After each swing, he says a few words to Dana Dahlquist, an instructor he’s recently started working with, who is standing with his arms folded across his chest a few feet away. Hovland is trying to explain what he wants his hip or his elbow to do, what his side bend might look like at impact, and where he wants his belt buckle to point. He made a hole-in-one during the Par 3 contest this morning, but the momentary joy that brought faded hours ago. Every few minutes, Hovland has to back away from the ball just as he’s poised to swing because a maintenance worker drives a cart in front of him, through the middle of the range, assuming players are done for the day.

Dahlquist’s watchful eye is a new element, but otherwise, the scene is a familiar one for Hovland in 2024. He has frequently been the last man standing on driving ranges, everywhere from Pebble to Los Angeles to Charlotte. Knight’s fellow caddies know, particularly during big tournaments, to pull together a plate of food for Knight when they’re wrapping up dinner because no one can guess how late Hovland’s practice sessions will run.

At 6 p.m., a security guard announces that the course is closed. Patrons needed to head toward the exit. That rule applies only to fans, however, not players. Hovland is just getting going. He continues launching fairway woods. Knight picks up Hovland’s launch monitor and takes it inside one of Augusta’s buildings, looking for an outlet to recharge it. They’d been at the range so long, that the battery had run down.

Hovland is still making swings an hour later when Augusta National turns on lights at the driving range. He can’t see the full flight of the ball in the air without them. The maintenance workers were wrapping up, but not Hovland. His range sessions have felt, at least this season, more like therapy sessions. By his own estimate, they have frequently hit the six or seven-hour mark.

Hovland is still pounding drivers toward the trees in the distance at 9 pm, trying to find something to feel good about, something that’s repeatable. Every time a ball drifts left, his shoulders slump. Knight goes to fetch more balls.

The following day, it looks like Hovland’s range session might have unlocked something. He makes four birdies on his opening nine holes, and surges near the top of the leaderboard. A miserable start to the 2024 season — just one Top 20 — might get washed away.

A rebuilt swing, however, is often like a stroll on a knife’s edge. On the 10th hole, Hovland sprays his approach way right, deep into the trees. He has to take an unplayable and makes a double bogey. He walks off the 10th green muttering to himself. Hovland scrapes his way around the back nine, finishing with a 71, but the frustration of the mistake seems to linger.

The following day, he bogeys the first hole, then triples the second. His drive on the 2nd hole is a nasty left pull into the woods, and when his third shot hits a tree branch, his face, his game, and his mood, seem to spiral from there. Hovland limps home, shooting an 81 (his worst score in a major) that is memorable only because he misses a six-inch bogey putt in frustration on the 15th hole, swatting at the ball with one hand after a missed par.

In recent months, Hovland has been telling people he knows he’ll work his way through this slump eventually, that he’ll find a swing feel he can trust. He’ll play good golf again, just like he did when he won the FedExCup and starred at the Ryder Cup. He’s worked through slumps before.

It’s just that right now, he feels so lost, he doesn’t see a way out.

There is no such thing as a perfect golf swing.

Ben Hogan did not have one in 1953, and Tiger Woods did not have one in 2000. They may have come close, but in golf, perfection is always fleeting. It manages to dance just beyond the grasp of its pursuer. The greatest golfers can occasionally touch it, but they never truly hold it.

Hogan and Woods both understood this. They chased perfection anyway. They would beat balls until their hands would crack and bleed, they would study their grips and their connection to the ground. They searched for secrets in the grass and the dirt, just to feel — a couple times per round — like the club and the ball had converged in perfect harmony.

Viktor Hovland may not have their golfing resumes, but he appears to be similarly wired.

He is a deep thinker and a frequent tinkerer. He craves information, and not just about golf but about science and aliens and conspiracies. When he gets curious about a subject, he likes descending down into YouTube rabbit holes in search of more. According to people who have worked closely with him, the things that make Hovland unique — that feed some of his genius — can also work against him at times.

He is manic about his work ethic, his prep, his diet, and his process. He is also, in the words of one person who knows him, one of the most stubborn people alive. On any given day, Hovland’s goal is to consume as much information as possible, then sort through what he likes, and apply it to his own game. He has been this way ever since he was a teenager growing up in Oslo, Norway.

“I just remember growing up and loving the game of golf and just started getting on YouTube and Googling stuff,” Hovland said. “I found a couple of guys that I liked, and then I started to learn what they teach, how they teach. Then that leads me to another guy, I start reading his stuff, see how that contradicts with the other guy, or maybe he has a different take on things. So it was definitely a huge process there of just trying to learn as much as possible.”

What is indisputable about Hovland is that he played some of the best golf of anyone in the world just six months ago, a season where he won three times, had two Top 10 finishes in majors, won two PGA Tour playoff events and was an essential cog in a European Ryder Cup victory.

“From the PGA to the Ryder Cup, there is no doubt in my mind he was the best player in the world,” said Joseph Mayo, Hovland’s former swing coach.

The season, however, still left him wanting.

Hovland was, even then, chasing a feeling he couldn't quite articulate. When he looked at videos of his swing from 2020 and 2021, he felt more in control of his shots. He wanted that feeling back.

“Sometimes in the game of golf you try to do the same every day, but then things aren't the same every day when you go to the golf course,” Hovland said during the week of the Masters. “I took a huge break after last year and when I came back, things were a little bit different and I had to kind of find my way back to where I think I'm going to play my best golf. And even at the end of the last year I still felt like, yeah, I was playing great, but I got a lot out of my game and it didn't necessarily feel sustainable.”

He was surprised — if he was going to be honest — that he was able to win the FedExCup. He still felt like he needed to make changes.

“That's kind of what I'm doing now,” Hovland said. “Sometimes you feel like you are making progress. I would say a little bit recently it hasn't been that satisfactory.”

Every golfer makes adjustments and tweaks to their swing throughout their career. Often, the adjustments are necessary, to compensate for injuries or how the body changes with age. Other times, it’s performance-driven, the desire to hit it farther, lower, or eliminate a troublesome miss. Occasionally, it’s aesthetic. A golfer will see their swing on video and hate the way it looks. No one tinkered as often, or as successfully, as Woods. He tore down and rebuilt the DNA of his golf swing multiple times, and had stints working with Butch Harmon, Hank Haney, Sean Foley and Chris Como during his professional career. But Woods’ successful evolution represents the exception, not the norm. Sometimes when you start messing with the sensitive dynamics of a singular golf swing, it can be difficult to put the pieces back together.

“Viktor has a tendency to go from teacher to teacher to teacher,” said Brandel Chamblee, the lead analyst for Golf Channel and NBC. “I know scores of teachers that message me saying that Viktor is asking them to help him with his golf game. Each one of those teachers thinks they’re the only teacher that he’s texting.

“The danger of going from teacher to teacher is that eventually you will stumble upon someone who will absolutely blow your mind with technical jargon, that will convince you they can solve every single problem. But it’s been my experience that more often than not, those teachers are method teachers. And they are far more interested in bending you to their method, thereby validating their method, than they are trying to get you to play your best golf through your own instincts, talent and experience. That’s the real danger. And I think that’s what’s happened to Viktor.”

To understand how Hovland could go from playing the best golf in the world to failing to break 80 at the Masters in a matter of months, it helps to understand the climb that got him to the summit of the game in the first place. The way he fell in love with golf in Oslo has been well-chronicled: his father, an engineer, had a temporary job in the United States near a driving range, and when the job in St. Louis ended, he came home with a set of golf clubs and gave them to his 4-year-old son. Eventually, his first loves, Taekwondo, soccer and skiing, faded away. Golf did not. By age 11, Hovland was obsessed. At first, the limited golf season in Norway, where courses were closed four months a year, was maddening. But it set in motion certain habits that are still apparent today.

For months at a time during the winter, Hovland could only feed his appetite for the game by hitting balls inside an old airplane hangar that had been converted into a driving range. It was the only place in the entire country where you could see the flight of the ball in the winter, although even that was limited to 80 yards off the clubface.

For someone with an intellectual mind like Hovland, hitting balls wasn’t enough. He needed to understand the golf swing, and the engineering behind it, so he went spelunking into the caves of online golf instruction. That led him to a little-known instructor working at a driving range in Hawaii named Kelvin Miyahira, and his first introduction to one of the most important theories of his life: kinematics.

“I would say kind of what got me really deep into it was I was reading Kelvin Miyahira's articles online when I was like 15 or 16, and he was kind of the first guy that I had seen that started to talk about kind of biomechanics in the golf swing,” Hovland said. “Before that, it was all just like, Oh, swing on the plane. Or oh, you're in or out or whatever. So I really liked just that level of detail into describing the golf swing, what the actual body parts are doing. And that obviously leads you to a different rabbit hole.”

If Hovland was, at least spiritually, like the music nerd desperate to find obscure recordings of bands who never quite made it big but still influenced those who did, then Miyahira was essentially his Velvet Underground. Miyahira — who gave lessons off of weathered, artificial turf mats, and based his teachings on what he learned about the kinetic chain by studying European javelin throwers — helped a light bulb go off in Hovland’s brain. His theories on the importance of “the spine engine” and the necessity of “right lateral side bend” remain essential pieces of Hovland’s swing, even today.

"I think it's neat to have an understanding about that stuff. The more information you have, in my opinion, it can only help you,” Hovland said.

It served as a catalyst for his rise through the European junior ranks, but as a teenager, he still wasn’t anyone’s idea of a sure thing. In 2013, when the Oklahoma State University golf program began recruiting another Norwegian, Kris Ventura, they happened to stumble upon Hovland too while watching the European Boys Championship. He was chubby and all of 5-foot-6, but his ball striking seemed exceptional. Head coach Alan Bratton kept thinking about him. As they recruited him over the next two years, they realized they were getting one of the most inquisitive minds in golf.

“I would say the biggest thing with Viktor is he’s his own man,” said Donnie Darr, who worked with Hovland as an assistant coach at Oklahoma State. “He forms his own opinions and his own thoughts. He isn’t afraid to be daring and try different things. He doesn’t feel like he has to do what everyone else is doing. He’s going to do what he believes is best for him until he decides that’s not the right path to go on. But he’s a very curious guy, always trying to get better. He never seems to be satisfied with where he’s at.”

As a freshman, Hovland was a good player, a freshman All-American, but he had noticeable holes in his game. He didn’t hit the ball high, he couldn’t hold firm greens. Launching a 3 wood high in the air was a nightmare. But each week, he put in the work to get better. He’d often pause his range sessions and do mirror work for an hour, obsessing over positions at different points in his swing.

“He immediately struck me as someone who wasn’t scared,” said Rickie Fowler, who got to know Hovland a little as an Oklahoma State alum. “He took a lash at everything. But away from the course, he was organic. He wasn’t trying to put on an act. He was goofy, and he made fun of himself, but he worked his ass off. He knows he’s not like other people, but at the same time, he’s genuine.”

As time went on, Oklahoma State coaches would make suggestions and Hovland would always listen. But he would only adopt the elements he agreed with. He also started working with a swing coach, Denny Lucas, whom he found on Instagram. Lucas helped him get steeper on the ball, helped him hit it higher, and it unlocked something special.

“One of the gifts I think he’s always had is he seems to have a very strong filter,” Darr said. “He’s willing to listen to people, willing to hear their side of things and think about it, and then decide if it works for him. He’s certainly proven over the years as he’s tried different theories that, as a coach, you kind of need to trust that he knows what’s best for him.”

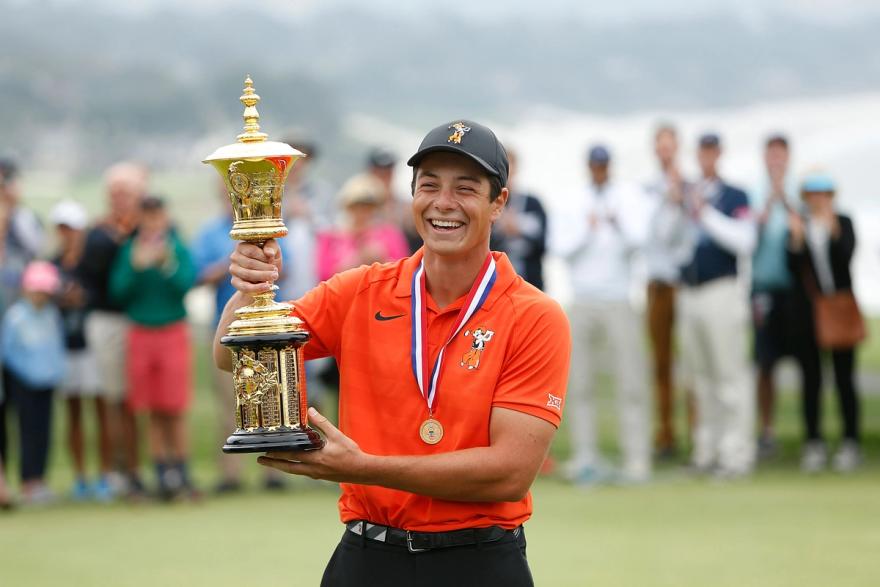

His methodical, stubborn, occasionally-scattered approach paid off handsomely in 2018 when Hovland was part of, arguably, one of the best college golf teams in history. The Cowboys won eight times during the regular season, then captured the school’s first NCAA title since 2006, going 5-0 in the finals against Alabama. Two months later, Hovland won the U.S. Amateur in dominant fashion, blitzing through the field at Pebble Beach and crushing Devon Bling 6-and-5 in the final.

“I always thought I had a good vocabulary,” Hovland said after the win. “But I’m at a loss for words.”

Even as Hovland ascended, turning professional in 2019, he couldn’t resist seeking additional opinions. Mayo, a teaching professional in Las Vegas who had built up a large and devoted following on social media under the handle @TrackmanMaestro, received a message from Hovland in October of that year, asking Mayo if he could take a look at his swing.

“He came out to see me at TPC Summerlin, and I watched him hit balls,” Mayo said. “He put on a ball hitting exhibition that was simply incredible. We went back to my house that evening and I had a few cocktails and kind of got a little loose lipped. I looked at him point blank and said ‘I will not be your golf instructor. You don’t need a golf instructor. If you want to come to Vegas and play poker and hang out and drink some bourbon, then I’m your guy. But we’re not going to do golf instruction because you don’t need it.’ ”

Hovland thanked Mayo for his candor, but the pep talk didn’t stop him from shopping around for additional opinions. He knew he needed work, particularly on his short game. His driving and his ball-striking were masking some of his deficiencies around the green, but his full swing was so good, even the best players in the world were taken aback when they saw it in person.

“I think the thing that struck me about Viktor is he was very sure of himself,” said Rory McIlroy. “When I think about myself in my early 20s, I was so self-conscious. I was so awkward and didn’t know at all what I wanted. He seemed so sure of himself. I loved his full commitment on every single shot. I felt like he needed to work on how to hit three-quarter shots, but he was already one of the best drivers in the world. From tee-to-green, he was so solid. He just aimed up the right side, had a little over the top move, and hit this flat bullet cut every single time. That was super impressive.”

Subscribe to No Laying Up Emails

If you enjoy NLU content, you'll enjoy NLU emails. We send our newsletter twice a month, and we send a Weekly Digest email. Get monthly deals, exclusive content, and regular updates on all things No Laying Up #GetInvolved

The chipping, however, was a problem. Even after Hovland won his first event as a professional, the Puerto Rico Open, he saw no reason to pretend otherwise. At that point, he was ranked 230th out of 231 players on the PGA Tour in strokes gained around the green and nearly threw away the win after two disastrous chips led to a triple bogey on the 11th hole of the final round.

“I just suck at chipping,” Hovland said in his post-round interview. “I definitely need to work on my short game, and I was 100 percent exposed there on that hole."

He went to see legendary swing coach Pete Cowen after his win in Puerto Rico, and Cowen tried to teach him to open the clubface more and use the bounce on his wedges, but the technique didn’t really take. Eventually, Hovland sent some videos of his swing to Jeff Smith, another teaching professional working in Las Vegas with a large online following (@radargolfpro). They’d met once, when Hovland asked for some thoughts on his putting stroke.

“Initially he was looking for some direction in his full swing,” Smith said during an appearance on the StripeShow Podcast with Travis Fulton. “I met with him, we did some work together, kind of gave me an opportunity to get familiar with how he moves and what he does in his swing. For me, it became more like: ‘Man, you’ve got it figured out already.’ ”

That relationship almost immediately bore fruit. Hovland won three times on the PGA Tour and twice in Europe over the next two seasons. With a win at the Dubai Desert Classic, he climbed to 3rd in the Official World Golf Rankings. He also got into contention for the first time at a major, beginning the final round of the 2022 Open Championship tied for the lead with McIlroy. (He faded to T-4 with a 74 on Sunday.) Along the way, he continued to build his reputation as one of the more thoughtful, mercurial players in the game. He learned he liked driving solo from city to city, and he liked visiting and looking at paintings with his headphones on.

“We’ve talked a bit about conspiracy theories,” said Sepp Straka. “I loved talking about that, and he loves talking about that. We’ve talked a lot about aliens. He got really into Stonehenge, and I thought he was kidding. But he was really into it. When we were at Wentworth (for the BMW PGA Championship), he drove like an hour to go see it.”

He wasn’t close to many Tour players, but he was friendly with everyone.

“He does things his own way, and that works for him,” said Matt Fitzpatrick. “I can’t speak highly enough of him. In my opinion, he’s quite a quiet kid. I’ve spent a ton of time with him — practice rounds, Ryder Cup dinners — but I wouldn’t say I know him, particularly outside of golf.”

As good as his driving and his ball-striking was, the short game remained a glaring weakness. Dozens of stories from that year were written implying Hovland had improved, that his chipping and pitching was no longer a liability, but the statistics told a different tale: At the end of 2022, he ranked 191st on the PGA Tour in Strokes Gained Around the Green.

In December of 2022, Hovland cold-called Mayo. He wanted to know if Mayo would be willing to take a look at his swing and offer some thoughts. Mayo’s reputation as a short game coach had only grown since they’d last communicated, but Hovland wasn’t just looking for short game advice. He wanted a full assessment.

“He sent me some swings, and within 10 seconds of looking at the first one, I hit redial,” Mayo said. “I said ‘What in the world is going on?’ I didn’t like what I was seeing at all. And he didn’t like it as well. He was displeased with the way it looked, with what the ball was doing, and I was displeased as well. That was the beginning of us working together.”

Mayo has been hesitant to talk about the year he and Hovland spent working together. He says he turned down “hundreds” of interview requests prior to agreeing to speak with No Laying Up, but he felt that enough time had passed that he was finally comfortable opening up. In doing so, he wanted to make one thing clear upfront: He is extremely appreciative of Hovland, who took him places he never could have imagined.

“I thank him for taking me to the highest level,” Mayo said. “He introduced me to things I’ve never seen before. That’s why I’ll always say: Viktor Hovland did more for me than I ever did for Viktor. I owe him a debt of gratitude I can never repay.”

There is no shortage of theories in golf instruction about the best way to teach the short game. What works for Phil Mickelson and Tiger Woods might not translate well for some golfers, and the same is true of Jason Day or Steve Stricker, even though those four players represent the pinnacle of very different approaches. On YouTube and Instagram, there are two dozen coaches promising to teach golfers their secrets, many of them competing for likes, views and subscribers, with information that can easily blend together if you scroll from one reel to the next. In recent years, the method of teaching players to open the clubface and slide the club under the ball — typically brushing or bruising the ground with the bounce of the wedge — has exploded in popularity.

Mayo’s approach is dramatically different, although he is adamant that he does not force anyone to deploy any particular method. Instead, he uses a TrackMan to show how certain strikes generate spin, and he believes maximum spin can only be deployed effectively by moving forward during the backswing. Instead of getting wide and shallow, Mayo says, you need to be effectively steepening the club path and your angle of attack into the ball.

“I don’t teach a method,” Mayo said. “I explain mathematics.”

Hovland immediately gravitated to the numbers. He liked seeing verifiable data in front of him. Minutes into their first practice session, Mayo says Hovland was hitting crisp, Tour-quality short game shots. The commonly-held belief that Hovland’s full swing approach — particularly the way he bowed his wrist in the downswing — made it difficult for him to chip was nonsense in Mayo’s opinion. He showed Hovland videos of Jordan Spieth, Dustin Johnson and Brooks Koepka chipping and winning majors. All of them bow their left wrist in the downswing.

“The steepest angle of attack I’ve ever measured, and I’ve measured a lot of them, is 17 degrees down,” Mayo said. “And that was Viktor Hovland hitting a perfect shot. I have never, ever, at any level, had a golfer come to me and say ‘Joe I’m a terrible chipper’ and when I put them on a Trackman, they’re 10 or 12 degrees down. It might be out there somewhere with Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster. But I’ve got a shitload of bad chippers that are 1 degree down, 2 degrees down, 3 degrees down.”

The months that followed felt, to Mayo, like he’d grabbed onto a rocket ship. Hovland finished 3rd at The Players Championship, then grabbed the opening-round lead at the Masters and remained in contention for much of the weekend. At the PGA Championship at Oak Hill, Hovland had a real chance to win his first major, trading birdies with Brooks Koepka much of the day, never flinching until a loose drive on the 16th hole found a fairway bunker. An agonizing double bogey by Hovland let Koepka pull away, but he came away convinced he was close to breaking through.

“Obviously learning from mistakes is key, but sometimes you get enough scar tissue in there, that's not great either,” Hovland said. “I don't feel like I've had that scar tissue.”

Hovland won the Memorial in June, but it was his final round 61 at the BMW Championship at Olympia Fields — a round that helped him leapfrog Fitzpatrick, Scottie Scheffler and McIlroy to win — that sent a message to the golfing world he was done messing around.

“Everyone sees Viktor as this jovial, bubbly, happy-go-lucky guy,” McIlroy said. “And he is. But he’s also got another side to him that’s ruthless. He’s got an edge. I don’t want this to come across as derogatory to Rickie [Fowler], because Rickie is an unbelievable human being. He’s so nice, which is a great quality in a person. But Viktor is like Rickie with a killer instinct. As soon as the gun goes off, it doesn’t matter who you are. If you’re friends with him or not friends with him. I feel like I knew it, but I really saw it in the last round at BMW. As soon as he got a sniff, he was all business. For a professional golfer, that’s such a good thing to have. Not too many people have both.”

Hovland and Mayo looked like the feel-good story of the instructional world. Mayo didn’t feel like he was teaching Hovland as much as he was unlocking something already there. Hovland started gaining shots around the green instead of losing them. Mayo was intense and always bursting with energy, and Hovland’s personality was laconic and subdued, but their partnership worked. They often ate meals together, even visited Graceland together when the PGA Tour came to Memphis. They loved talking about their quirky shared interests — UFOs, ghosts and poker. “He’s a foodie and he loves Greek food, so he’d take me to his favorite Greek restaurants,” Mayo said.

When Hovland won the Tour Championship in August, getting up and down from the bunker for a final round 63, he bear-hugged Mayo as he came off the 18th green. “That’s when I knew ‘This kid is the best player in the world,’ ” Mayo said. “Without question, that was the best moment.”

Hovland gushed about his swing coach in the winner’s press conference.

“I like picking people’s brains, and he’s an interesting brain to pick,” Hovland said. “Ever since he’s been on the team, it’s been great to have someone kind of look at my game from a completely different standpoint. He might be one of the only instructors that never watches golf. So when he came on board, he had no idea how I played, what it was doing, what it looked like. He kind of had a fresh set of eyes. I do like to try new things because it’s fun.”

Hovland finished 2023 gaining strokes around the green for the first time in his career. It wasn’t by much (+0.08) but just being an average chipper solidified his spot as one of the best players in the world. When he chipped in on the opening hole of the Ryder Cup, even his American opponents were in awe. They understood how far he’d come.

“Everyone out here can appreciate how much time and work he’s put into that,” Fowler said. “That doesn’t happen overnight. Yes, you could go hit that shot when you’re working on something on the range. It’s easy because you’re free. But when you’re able to put the amount of reps in that you can pull it off in competition, on the biggest stage, that says a lot. He works his ass off. And he loves the grind.”

It felt like 2024 couldn’t get here soon enough.

In November of 2023, Mayo says he got a call from Hovland.

It was time, Hovland said, for them to part ways.

“He said ‘Joe thank you for what you did. Without question, I wouldn’t be the player I am without your help. But I just want to do it on my own,’ ” Mayo said. “I said ‘Viktor, I love that. I want you to do it on your own.’ There was no fighting, no animosity, no bad blood. Nothing like that.”

Mayo insists he wasn’t upset. He’d been predicting — even hoping — that day would come eventually.

“My number one goal with this kid was for him to no longer need me,” Mayo said.

He’d told several friends during the year they’d spent together that once Hovland got his swing dialed, he wouldn’t need Mayo any longer and that was the way it should be. Mayo wasn’t interested in getting famous. He never wanted to be the guy nudging his way into the frame every time Hovland held up a trophy. A good teacher, he believed, has succeeded when the pupil feels confident enough to walk alone.

That said, Mayo has been reflecting on their time together in recent months. He’s come to understand some things about himself.

“I admit that I have a very strong personality,” Mayo said. “I am hard to take in large doses. That’s one of my many many flaws in life. I realize being around me (for) a year full time, like we were, is probably pretty tough. Without question, I know I am hard to handle for a long period of time. When he said he wanted to do it on his own, I was relieved.”

Mayo said he suspects that working with him is not all that different from the way Indiana University basketball players felt having played for coach Bobby Knight.

“It’s something I've struggled with my entire life,” Mayo said. “I’ve been this way since I was a young man. We’ve all got flaws, nobody is perfect. People who know me will tell you ‘Joe is intense, Joe is tough, Joe is hard to handle.’ I guess what I’m trying to say is this: If I had to be honest, if you threatened me with going to prison if I wasn’t honest with you, then I’d say my personality was probably part of Viktor wanting to do it on his own. I admit that. I admit that my strong personality is a turnoff to some people at some point in time. I’m taking the blame, if you will. I’m man enough to admit that, man enough to sack up and say being around me for a year was probably a lot to handle.”

Hovland has declined several opportunities this year to share his perspective on why he and Mayo split. He has, in fact, been reluctant to give many interviews as he works through his current malaise. In March, he started working with Grant Waite, a former Tour pro.

“I’m a very curious guy. I like to ask questions,” Hovland said, prior to the Arnold Palmer Invitational. “Sometimes when you ask a question and you get some answers, that leads you down a different path and opens up some new questions and you pursue a different path. I just want to kind of see where it goes. I always like to improve and expand my knowledge, and it just happened to lead me down to Grant Waite.”

By April, he and Waite had parted ways. He began working with Dahlquist, a biomechanics expert who has worked with Bryson DeChambeau, and teaches at a public golf course in Long Beach. Hovland says he’s still trying to find his way back to the swing he had in 2020-21, when he loved the flush feeling he had of the ball coming off his clubface. But admittedly, that was a handful of swing patterns ago.

“The kind of frustrating part is when you're trying to figure things out and you don't necessarily see the progress or you don't know exactly if this is the right road ahead,” Hovland said.

Searching for a feeling with his irons has left him with very little time to work on his short game, and as a result, his chipping is as bad as it’s ever been. His Strokes Gained: Around the Green in 2024 is -0.74, easily the worst mark of his career. He is 186th on the PGA Tour in that category this season. Only France’s Paul Barjon (-0.75) — the 257th-ranked player in the world — is worse among players with enough qualifying rounds. He’s 179th on Tour in sand save percentage. At The Players in March, he lost -1.75 strokes around the green, the second-worst number of his career for a single tournament, and the fourth-worst number posted by any player in a PGA Tour event this year.

Multiple people who have spoken to him in recent weeks say he seems despondent, that it’s almost like a light has gone out behind his eyes. After missing the cut at the Masters, he withdrew from the RBC Heritage and didn’t enter a tournament for almost a month. He returned for the Wells Fargo at Quail Hollow, but there were still major holes in his game. He finished T-24, 18 shots behind McIlroy.

One person who knows Hovland well and speaks with him often believes Hovland has become ensnared in a web of his own curiosity, that he’s now trying to blend different thoughts from different instructors. He can’t resist going down endless YouTube or TikTok rabbit holes, and now something has short-circuited in his brain.

“I think what made him and Joe work is their crazy kind of aligned,” said the person, who asked for anonymity so they could speak freely. “Viktor can be kind of arrogant about what he knows. Joe was able to tell him when he was wrong. And Viktor was willing to buy into the program.”

Mayo doesn’t watch much golf, and he hasn’t watched Hovland this year, but he’s convinced Hovland will work his way through his current miseries. He’s far too talented, Mayo says. Fretting over a rocky five-month stretch is going to seem ridiculous once he finds a pattern that he’s comfortable with.

“He will win again. I have faith in him, and I have faith in his golf swing,” Mayo said. “I have complete faith in him.”

Hovland has little interest in money, according to someone close to him. He’s become frustrated with the unending rumors he might be headed to LIV, and the constant cycle of denying them. It’s true he’s been unhappy with PGA Tour leadership, and has made that clear, but he wants to focus on golf, and the pursuit of history. His friends believe he’s going to find his old self soon, maybe even come out of this quest stronger than ever.

“He literally doesn’t care about anything except trying to see how good he can be at golf,” Darr said. “He doesn’t need a fancy car, he doesn’t need a fancy house. He doesn’t need things. He’s completely driven to see how good he can become. He’s driven to reach his full potential, and I think that’s why you see him going through these swing changes. It’s not even about winning the FedExCup. He knows that wasn’t his full potential. He knows ‘I can do better.’ Everyone goes through struggles, even Tiger. It’s a hard, lonely game. He’ll be back to full strength soon.”

Chamblee is less certain. The night Hovland was hitting balls at Masters under the lights, Chamblee and his colleagues Rich Lerner and Paul McGinley were on the left side of the driving range, filming an episode of “Live From” for the Golf Channel. As the evening wore on, it was hard not to steal glances at Hovland and wonder how long this would drag on.

“The same thing that helped Viktor lose his way is the same thing he thinks will get him back, and that’s a terrible place to be,” Chamblee said. “There is so much information readily available. You can be on the range and pull up YouTube. I’m on YouTube all day, but I’m not trying to discover some secret. I’m trying to look at players’ golf swings so I can discuss it. But at every turn, I find conflicting information.”

Chamblee said he was just talking to a teacher within the last two weeks who said Hovland was texting him video of swings asking for thoughts, even though he was still supposedly working with Dahlquist.

“The reason Viktor won’t commit to any one of these is I think he believes if he talks to 20 of them, he’s clever enough to figure out their commonalities,” Chamblee said. “Then he can go work with one for a little bit, then another for a little bit. Well, it’s a whole army of guys who are spinoffs of Mac O’Grady. I disqualify every teacher if they put one swing of Mac O’Grady on their Instagram."

"I saw Dana Dahlquist at AmEx this year, and I like him, he’s a nice guy, but I asked him: ‘What are you doing putting up swings of Mac O’Grady as if that represents an ideal swing that anybody should ever try to emulate?’ Mac O’Grady was an average-to-terrible ballstriker who could hit 7-irons 200 yards because he de-lofted everything. I looked up his data. Watched him ruin Seve [Ballesteros]. I watch him try to ruin Tom Watson. I watched him ruin Jodie Mudd. And you put his golf swing up like he’s some evangelist? That’s a sign to me that they’re all method teachers. They’re all little minions.”

A great golf swing, in the end, might be like a magnificent painting, the kind that Hovland used to stare at in museums, back when he had the time. Before any artist begins to paint, it helps to understand the importance of basic elements like composition and brush strokes. A teacher is invaluable at this stage.

But ultimately, art is singular to its creator. It’s not the work of a committee.

A painting needs to be cared for and maintained, at worst carefully restored to its original glory if it starts to deteriorate. But if you can’t leave it alone, you risk muddying it to the point where the elements that once made it brilliant are harder and harder to recognize. It becomes a curiosity. Maybe even a cautionary tale.

Kevin Van Valkenburg is the Editorial Director of No Laying Up

Email him at kvv@nolayingup.com

Join The Nest

Established in 2019, The Nest is NLU's growing community of avid golfers. Membership is only $90 a year and includes 15% off at the Pro Shop, exclusive content like a monthly Nest Member podcast and other behind-the-scenes videos, early access to events, and more newsletter-exclusive written content from the team when you join The Nest.