This is the first in a series of what we’re calling NLU Special Projects. In each edition, we’ll do a deep dive into one particular topic, unpacking it in ways you may not have considered previously. This piece was conceived as a podcast — and we’d encourage you to listen to it in that format — but we also wanted to make a print version available for all you luddites out there.

For our inaugural episode, we explore the Tall Tales of Gary Player.

Thanks for reading and listening.

Morning, Damon!

In 2015, The U.S. Open was held in the Pacific Northwest for the first time in its history. The venue was Chambers Bay, a public course designed by Robert Trent Jones Jr., that was built on top of a sand-and-gravel quarry, on the shores of Puget Sound. A links-style course with little rough and even fewer trees, it represented a dramatic departure from the tournament’s recent traditions. The fairways were muted and brown; the tall, wispy grasses that lined the course’s numerous bunkers were a stark change from the U.S. Open's typically suffocating rough. From the highest point on the property, you could see miles of calm blue water and sky.

Despite the fact that the tournament boasted a star-studded leaderboard, and that it was ultimately won by one of golf’s rising stars — 21-year-old Jordan Spieth, who just a few months prior had won the Masters — reviews of the course were decidedly mixed.

Henrik Stenson said the greens were like putting on a field of broccoli. Rory McIlroy said a round at Chambers Bay felt like you were playing on the surface of the moon. Several players described the conditions, particularly the greens, as a disgrace and said the USGA should be ashamed.

But the harshest criticism of the course came from someone who wasn’t even competing in the tournament. On Saturday morning, prior to the third round, Damon Hack and Gary Williams of the Golf Channel welcomed nine-time major winner Gary Player to the show, eager to get the 80-year-old Hall of Famer’s thoughts on the peculiar U.S. Open that was currently unfolding.

Player, who did the interview remotely from Chambers Bay’s driving range, was grinning as the camera cut to him. There was no indication he was about to unleash one of the most famous course critiques — and diatribes — in modern history, particularly after Hack opened with easily the most benign question to ever inspire a 7-minute monologue:

“Good morning Mr. Player, how are you?”

Morning Damon! And morning Gary! I’m standing in the most beautiful state in the world. Washington. Seattle here. Unbelievably beautiful. And we’re playing the U.S. Open, this great championship. A group of people that I have great respect for. But this has been the most unpleasant golf tournament I have seen in my life. I mean the man who designed this golf course had to have one leg shorter than the other! It’s hard to believe that you see a man miss the green by one yard, and the ball ends up 50 yards down in the rough. And can you imagine? This is a public golf course. This is where we’re trying to encourage people to come out and play and get more people to play the game. They’re having a putt from 20-30 foot and they’re allowing for 20 foot right and 20 foot left. I mean it’s actually a tragedy.”

He continued for several more minutes, invoking his desire to save the environment, to save amateur golf, to save marriages by helping husbands return home sooner to their wives, but it was Player’s hyperbolic use of the word “tragedy” that would stick with me and my friends.

It was so absurd, we couldn’t resist taking it even further, inventing a parody of Gary Player where nothing felt off-limits. By week’s end, I’d re-imagined his monologue in a cringe-worthy South African dialect, pretending he’d called the course “Chambers Bay of Pigs” and that it was basically “the 9/11 of courses.”

By 2015, golf media was in the midst of a seismic shift, though few people fully understood it at the time. Newspapers were slashing travel budgets; the make-up of the press tent was rapidly changing. Younger voices, many of us buoyed by our Twitter followings, were filling the void with humor and irreverence, and raising a new generation of golf fans on a steady diet of podcasts. Virtually none of us had been alive during Player’s prime.

I was an exception, but only technically. When he won the 1978 Masters, his ninth and final major, I was three months old.

For that reason — and a dozen others — we did not view him with the same reverence we did Arnold Palmer or Jack Nicklaus. Player was a curiosity, a Paul Bunyon-esq figure more famous to our generation for appearing naked on the cover of ESPN The Magazine than he was for winning any of his majors.

When I began appearing regularly as a guest on this podcast, Soly couldn’t resist goading me into sharing my Gary Player caricature with the audience. The goofball in me who grew up idolizing the impressions done by Dana Carvey and Phil Hartman was happy to oblige. Everything that came out of my mouth felt a little ridiculous, and increasingly cringe, but none of it felt dishonest.

(Here are the receipts.)

KVV: That take was despicable, Porath! I can’t believe you would call out Jordan Spieth like that and say he lacks pop!

Soly: What about the crowd? What did you think of the crowd Mr. Player?

KVV: The crowd was horrendously spirited! And tragically into it! Hopefully next time they have a Ryder Cup in the United States – I personally never played in a Ryder Cup, but if I did, I would want Fatty Patrick Reed to lose a few pounds and play with me, he would be a great partner, if he took on my gluten free diet.

I wasn’t mocking Player so much as I was embracing a version of him that felt spiritually true, even if in reality, it was more like the kind of SNL skit they air just before 1 am.

Soly: Last one, I want to get your thoughts Mr. Player on CBD oil. It seems to be all the rage on the circuit. Have you dabbled in it at all yourself?

KVV as Gary Player: CBD oil? I’ve never heard of such a thing. Sometimes I’d go to the garage and take a little sip of motor oil and say how tough is Gary Player? Let’s see if he can just process this right through or if he’ll be rolling in pain and lose five more pounds that he can’t drop.

Besides, it was hard enough to discern where the line between fact and fiction existed for Player. Early in his career, he would boast that he did 300 crunches every morning as part of his routine to stay fit. Later on, that claim rose to a thousand crunches four times a week. In his 80s, he insisted, with Orwellian certainty, the routine had always been thirteen hundred per day. In 2022, he told the New York Times he’d shot his age or better Twenty-four hundred (2,400) times in a row. In 2023, he told the same story to the Palm Beach Post, only now he claimed that number was three thousand and seventy two (3,072) times in a row.

It wasn’t that Player was lying — framing it that way felt nefarious — but it reminded me of a passage in one of my favorite short stories, Tim O’Brien’s Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong, a meditation on war and storytelling.

“It wasn't a question of deceit,” O’Brien wrote. “Just the opposite: he wanted to heat up the truth, to make it burn so hot that you would feel exactly what he felt. Facts were formed by sensation, not the other way around, and when you listened to one of his stories, you'd find yourself performing rapid calculations in your head, subtracting superlatives, figuring the square root of an absolute and then multiplying by maybe.”

The only way to make people understand what Player had put himself through, what he had sacrificed and overcome, was to fill every tale with Biblical details, like it was a chapter in the Greatest Story Ever Told.

It wasn’t just that he’d befriended Nelson Mandela. It was that he kissed Mandela’s feet when he first met him, that he spoke up at the height of apartheid and insisted that his hero be released from prison, and he didn’t care if he was branded a traitor. That the arc of their friendship was a bit more complicated was not important, at least not to Player. That is how he remembered it.

At some point, I realized that despite all my jokes, I knew little more than the basics about Player’s life. I knew he was an important figure in the game’s history, arguably the most important player born outside the United States. But I knew far more about the exploits and accomplishments of Palmer, Nicklaus, Woods, even Tom Watson and Phil Mickelson. It felt like an embarrassing oversight, and one I intended to remedy.

The more I read about Player, the more I realized I likely wasn’t alone in my ignorance, at least among my generation of golf sickos. The best Gary Player stories seemed buried in books or magazine archives. They hadn’t matriculated to podcasts — at least not yet.

Player — now 88 years young — is showing few signs of slowing down. He has lived such a long, colorful, strange life, it seemed worth examining, particularly while he is still with us. Then again, it’s possible Player may outlive me. He has never been shy about critiquing the health and fitness of journalists.

“It just amazes me to see a young man like that, 50 pounds overweight,” he once told a reporter from the magazine Today’s Golfer, referring to the previous journalist who’d just interviewed him. “Why can’t he realize that he’s going to die? He’s such a nice man, obviously intelligent – he asked very good questions – but he’s going to die. He’s going to get diabetes, a heart attack or cancer, and within 10 years he’s going to die. The doctors, they’re bastards. Doctors should be saying to him, ‘Look, you’re going to die. You’ve got to stop eating.’ I find it fascinating.”

By the way, I’m not doing the Gary Player impression throughout this podcast. Listening back to some of those, we've exhausted that bit.

In December of last year, I went to work, vacuuming up as many stories as I could, sifting through three dozen sources, trying to cross reference or fact-check both the outlandish and the absurd.

Eventually, I realized it was a futile exercise. Every Gary Player story, whether it was real or embellished, had a purpose.

What he FELT was just as interesting as what may have happened.

And what he wanted YOU to feel, as the listener, was usually the most revealing part of the story.

Gary Player meets the world—just kidding. The world meets Gary Player.

Gary Player was born in 1935 in Lyndhurst, a small village that once sat a dozen miles outside of Johannesburg, South Africa, before the city grew and essentially subsumed it.

His ancestors, he believes, were of French and English stock, and he credits them for his large brown eyes. In 1838, his great-grandmother was part of a large wagon train that was making it way through the territory of Natal, and seeking safe passage to the coastal plains of South Africa, when the leader of the caravan, Piet Retief, attempted to parlay with Dingane, the King of the Zulus.

“Dingane murdered Retief and his men, then fell on all the wagons, massacring women and children,” Player wrote in his 1966 autobiography, Grand Slam Golf. “My great-grandmother was stabbed in the side by a Zulu spear, but somehow dragged herself into the bush, and survived.”

It would not be the last time that fortitude would play a role in his family lore. Player’s father, Harry — whom everyone called Whiskey — went to work in the Johannesburg gold mines at age 13, and he spent 30 years working below ground, every day riding an elevator that descended 10-12,000 feet below the surface, praying he would return at shift’s end and see the sunlight.

“I went to visit him one day,” Player told Golf Digest in 2010, "and when he came off the "skip" — the elevator that lowered them into the mine — he immediately sat down. He took off his boot and poured water out of it onto the ground. I asked him where the water came from, and he said, "Son, that's perspiration. It's hot as hell down there." He told me how men died like flies in those mines. He said a miner's best friend was the rat, because when the rats took off running, it meant a cave-in was imminent. Every day the workers gave the rats bits of their sandwiches as tribute.”

Player spent much of his childhood outdoors, the youngest of three children, learning to love the land and unpack its mysteries. There was a pear tree in his yard, and from one of the branches, their father hung a rope. He and his older brother Ian took turns racing to the top, the muscles in their arms and shoulders hardening with each climb. “If Ian did it once, I would do it twice,” Player said. “If he did it twice, I would do it four times. If he jumped five feet, I would try to jump ten.”

(By the way, decades later, Gary Player went back to that house, climbed that tree, cut down that rope and took it home with him as a keepsake. That’s how crazy Gary Player was.)

He worshiped Ian, who taught him how to shoot an air rifle and a catapult, skills he believed eventually translated onto the golf course.

“I was exceptionally good with a catapult as a young lad,” Player wrote in Grand Slam Golf. “I could knock over a bird once in three shots, at distances up to 50, 60 and 70 yards, and I don’t suppose one person in 50,000 can do that. I don’t boast about it — it was a fact of life.”

"That's a sissy game"

When Player was eight years old, his mother, Muriel, died of cancer. He was too young to understand what was unfolding, though he knew she had been sick for some time. “[My sister] Wilma has told me how in the closing months of her life, she was in great pain,” Player wrote. “But when people asked her how she was, she would say ‘Just fine’ or ‘A little better today.’ Wilma, who knew this was not true, would often chide her for this, and ask her why she said it. She would always answer ‘People don’t want to hear you complain. They have their own troubles. And they feel better if someone else says she feels better.”

Player told Golf Digest that for years, long after he became an adult and had a family of his own, he would wake up sobbing in the middle of the night, dreaming of her.

“Deep inside,” he said, “we all want and need our mothers.”

As a boy, he would dig golf balls out of the mud with his feet from the pond at his local course, then sell them by the dozen. But he had no interest in playing the game. He preferred rugby and cricket, swimming and soccer. But at age 14, Player’s father surprised him one day by asking him if he wanted to play golf.

“Dad, I don’t play golf, that’s a sissy game,” Player told him.

Somehow, his father persuaded him to come along anyway. The first three holes of his first-ever round, Player recalled, he made three consecutive pars.

“Then I got down to all the eights and nines and four putts and all the rest, but it was a fair start to the ‘sissy’ game,” Player wrote.

Within a month, he was hooked, taking countless swings (without a ball) off a rubber mat in his garden. Eventually, he discovered the local course at Virginia Park. One afternoon, he peeked his head over the fence and saw a 13-year-old girl hitting balls under the watchful eye of the head pro, her father. The girl, Vivienne Verway, would become the love of his life. The second time he saw Vivienne, he told his brother he was going to marry her. It turned out he was right. Within a few months, he’d proposed, but suggested they wait until he had enough money to support a family. He was, after all, 15 years old.

Golf, he believed, was his ticket to fame and riches. He wanted to own a fancy car, and maybe even a farm someday. When Player informed his father of the plan, Whiskey Player all but collapsed. He had promised Player’s mother, on her deathbed, their son would finish his studies and go to university. But Player was stubborn. In his autobiography, he said that he told his father: “I want to be a professional golfer and this is my life and I want to do it.”

He quickly learned it would not be an easy road to travel, particularly for a poor miner’s son. He played with used clubs and used golf balls and had little money for lessons.

Player’s father told Sports Illustrated: “I would have had my chips under all that pressure. Not him. Oh, when it was just the two of us out there we bloody well had our fights, all right. He'd tell me he couldn't make it, and I'd tell him he was talking rot. I'd tell him he was falling back off his shots, and he'd say, 'I don't want to hear it,' and I'd say, 'Well, the hell with you,' and then later he'd put his arm around me and kiss me and say, 'I'm sorry, Dad, I just got to explode sometime and you are the only one who can take it!' "

He climbed his way through the amateur ranks, hitting wild hooks off the tee but still finding ways to score. In certain tellings of this time period, he never once doubted his destiny. In others, doubt bubbled to the surface. He was wiry and strong, but grew to only 5-foot-7, seemingly half the size of his father.

“Dad, I'm too small," Player one day complained.

"Nonsense," his father said. "It all depends on the guts you have. It's what's inside of you that matters."

He would practice as long as there was sunlight, and sometimes even when he had missed the cut. At the 1955 South African Open, he failed to qualify but refused to leave the putting green in his frustration, practicing until ten o’clock at night.

“Look at this little idiot, wasting his time,” his father heard someone mumble. “What does he think he’s doing? He’ll never get anywhere.”

Listening to Gary Player tell one of his most famous stories, about the first time he left South Africa in an attempt to qualify for the 1955 Open Championship at the Old Course, feels a bit like listening to someone recount Odysseus leaving Ithaca to join the Trojan War.

He was nervous, but he knew it was what his destiny called for. Members of his golf club had raised the money for his airfare. Before he left, Player’s father handed him 200 pounds for the week, money he later learned was an overdraft from the bank, a leap of faith. When Player arrived in St. Andrews, he realized he had no place to stay, so he inquired about a hotel. The cheapest available that night was 80 pounds. He was shocked.

He dressed, instead, in his waterproofs, found a spot among the dunes, and slept in the West Sands, the windswept beach next to the Old Course. He slept beside his clubs. In his suitcase, he’d packed two pairs of pants, two shirts, two sets of underwear and a black knitted tie that he would wear to dinner, but use as a belt by day.

Years later, Player said: “It was the greatest thing for me really to struggle like that. Because the word that takes over — which is an essential ingredient — is gratitude.”

He failed to qualify, ricocheting his opening tee shot off a fence post because he was so nervous. The starter, he remembered, laughed at him.

But the experience was invaluable. He returned home, redoubling his practice routine. In 1956, he won four times, including the South African Open, and finished 4th in the Open Championship at Royal Liverpool. When he won the Ampol Tournament in Victoria, Australia, he sent home a telegraph to Vivenne with just one sentence: “Buy the dress!” The $5000 first-place check meant they now had enough to get married.

Globetrotting Gary

His dreams were starting to crystalize. In 1958, he finished 2nd in his U.S. Open debut, four strokes behind Tommy Bolt. He finished 7th at the Open Championship. He won for the first time on the PGA Tour, at the Kentucky Derby Open, and captured the Australian Open, his biggest win to date. He began developing a reputation as a man who would fly anywhere in the world to tee it up.

“I had to go through six different layovers to get from Johannesburg to the United States to play a tournament,” Player told the New York Times in 2012. “I often traveled with my family, which, aside from my wife, also included, at some points, six children. There was no such thing as a disposable diaper or a changing table. I had to get to America and win the tournament so I could make enough money to break even and get a return flight. I wasted a lot of life sitting in an airline seat. We calculated it once, and it came out to about three years.”

His methods for improving his craft were unorthodox, to put it lightly. Some days, he would purposefully tailgate the slowest driver on the highway, even if he had somewhere to be, trying to achieve a state of zen. Other nights, he claimed, he would stand in front of the mirror in a Thai Chi position and slap himself repeatedly, just to teach himself patience.

Sports Illustrated once asked him what he saw when he looked in the mirror.

"What I would see," he says, "is just the opposite of what I am. Basically I love to laugh. I love people. I like to have people like me, to have friends. But what I would say of the person I would see out there is, 'Well, he is a battler.' I am too sentimental, I suppose. I am not scared to fight for anything or to fight anybody.

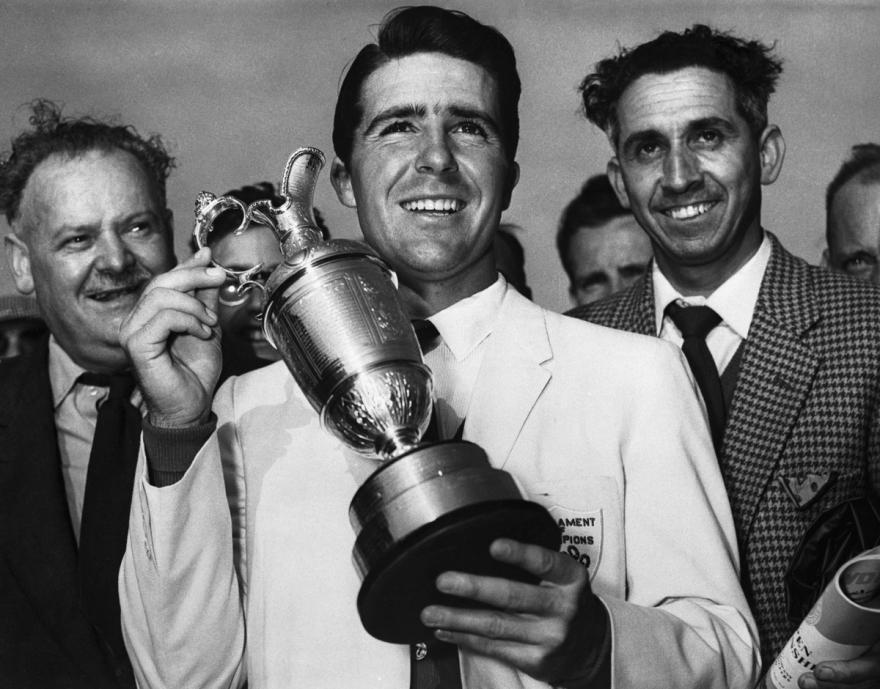

In 1959, a decade of hard work culminated at the Open Championship at Muirfield. He trailed by eight strokes going into the final 36-holes, which back then were played all on one day. But he told a friend the night prior he had a sense something special was unfolding.

“Tomorrow you’re going to see a small miracle,” Player said. “In fact, you’re going to see a large miracle. I’m going to win the British Open.”

He climbed the leaderboard with a round of 70, then went on a tear over the final 18. Player came to the final hole needing only a par to shoot 66, but with only a vague idea of where his closest competitors stood. A four would likely win the Claret Jug.

Then, to his horror, his drive on 18 found a pot bunker.

“I made six, and my entire world seemed to disintegrate,” Player wrote. “I had the British Open Championship all but packed up in my bag and I finished with a miserable six.”

He stormed off the 18th green, signed his scorecard and rested his head against a shed. Vivienne put her arms around him, attempting to console him. In his book, he included a picture of the scene and could resist addressing it. “It is reported that I cried. I didn’t. But I certainly felt like it, not so much out of self pity, but from sheer anger and temper with myself. To have botched a great round, to have squandered a championship in that way, was criminal.”

He retired to his hotel, still furious and in need of a stiff drink. As scores began to trickle in, his friends encouraged him to return to the course, but Player refused. He snapped at a friend: “Remember when Sam Snead threw away the U.S. Open with an eight and has never won it to this day? Well I’ve just done that today. I’ll never win this British Open.”

He was wrong. His closest pursuers, Fred Bullock and Flory Van Donck, struggled in the windy conditions. Players’ friends eventually persuaded him to return to the course as they were coming up 18. It turned out each man needed a birdie to tie. Neither came close.

At 23 years old, Gary Player was the youngest winner of the British Open since 1868. In those days, it was the responsibility of the winner to commission someone to engrave his name in the Claret Jug. When Player returned the jug to the R&A the following year, they noticed his name had been engraved larger than any of the previous winners.

He was determined to be remembered.

“Of the victory, Player wrote: “All the long hours of sweating in the South African sun, all the work and travel, all the faith that my wife and family and friends have shown me over the years, had been justified,” Player wrote. It seemed like a marvelous ending. But it was only a beginning.”

The real Gary Player

Gary Player promised his father he would quit playing golf when he was 35. That he would retire comfortably, and live out the rest of his days running a farm.

It proved to be a hard promise to keep.

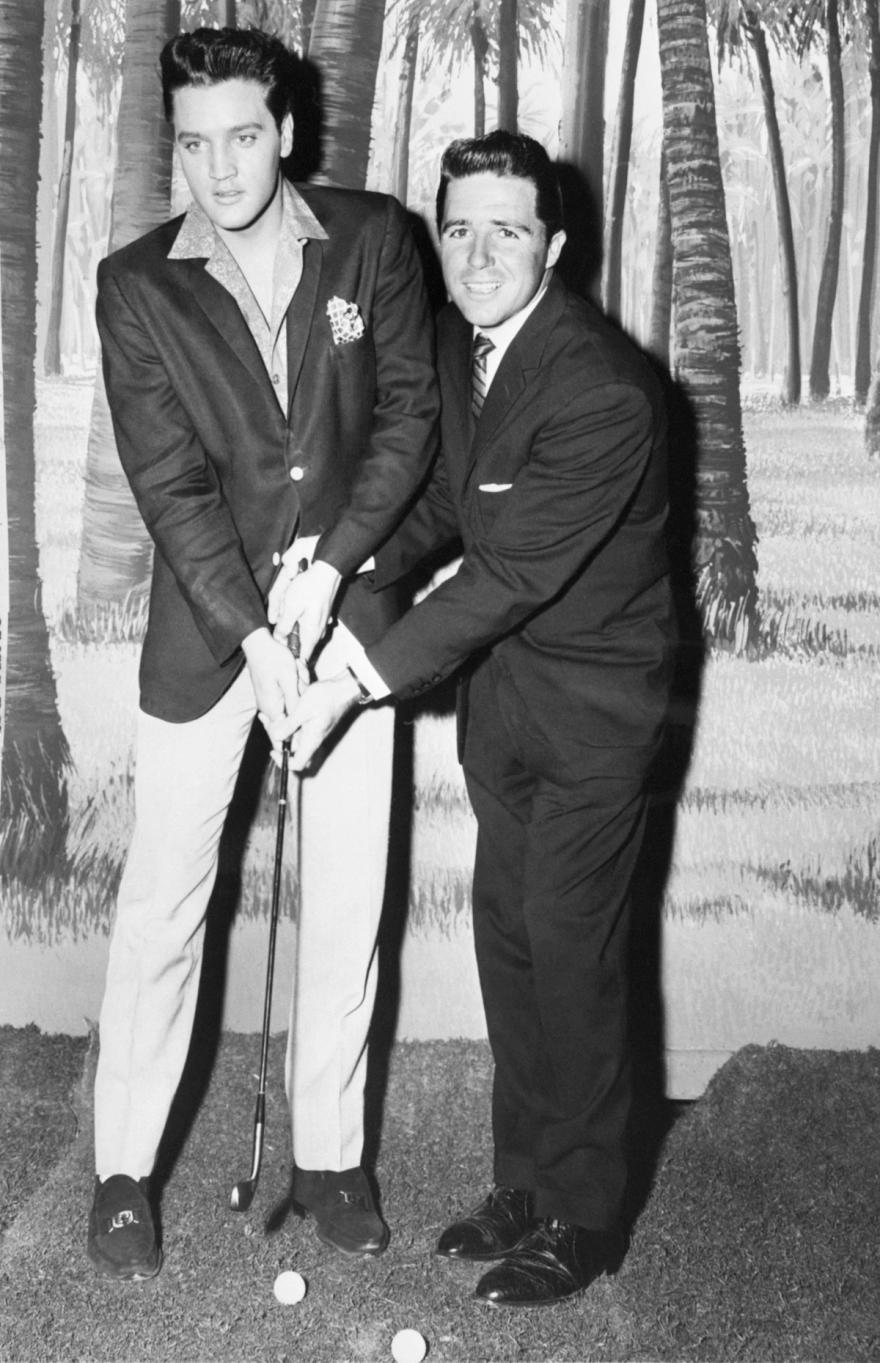

When he followed up his Open Championship victory in 1959 by becoming the first foreign-born man to win the Masters in 1961, his financial health changed dramatically. There were offers from equipment companies, offers to play a series of televised matches against Arnold Palmer, clothing and golf ball endorsements. After he appeared on the Ed Sullivan show, his manager received a telegram from Elvis Presley, insisting that the two men meet.

“I walk in there and he’s doing a movie called Blue Hawaii,” Player recalled. “As I walk in there he says ‘Cut!’ I had a tie on and a jacket and I was going to meet the King. He goes in the room and puts on a jacket and he comes out with that southern accent and he says ‘How do you do, sir?’ He says ‘I want to play golf.’ Well he had a grip that looked like a cow giving birth to a roll of barbed wire. … So I get his grip right. He says ‘What’s important?’ I said Elvis, you’ve got to use those hips now. You’ve got to wind up with the hips and unwind with the hips. He says ‘You’re talking to the right man, dear boy. And he gives that little lead and goes zip zip zip zip zip! You know how he moved those hips? Man could he move those hips.”

But even as his celebrity grew, his heart remained tethered to South Africa, particularly after he was able to purchase a farm where he could breed racehorses.

"You must go up and see my farm," Player told a writer from Sports Illustrated. "Then you will realize how wonderful a life that is. On my word of honor, it is so beautiful up there it is fantastic. The trees, the mountains, the horses. You are really living when you are farming. It's true. I would rather farm than play golf. I would rather ride a horse than play golf.”

His friend George Blumberg told him he did not buy it.

Sports Illustrated captured Blumberg teasing his friend, quote: “It is my opinion that you would be a fine farmer for about two months, and then you would read in the paper that someone else is the best golfer in South Africa, and you would come running down out of those hills as fast as your little legs would carry you. That is what I think of your farming, Gary Player."

The manual labor a farm required, however, had unlocked ideas in him about healthy eating and strength training. He had cut out all processed foods, and had begun treating his body like an instrument. Not a guitar or something disposable, but something both powerful and rare, like a stradivarius. His rivals might be longer than him off the tee at the moment, but he was convinced he would catch them.

As Player told Sports Illustrated: "You have to remember that I expect to be out-driven by Arnold and Jack, so it doesn't bother me. Arnold weighs 25 pounds more than I do and Jack 50 pounds more. Yet I'm confident that by the time I'm 30 I'll be hitting the ball almost as far as they do—not quite as far, but almost. This is because I have started doing my exercises again. Every day I can feel myself getting a little stronger. It's amazing what a man can do with his body in three years by exercising. Until about a year ago I was doing a lot of push-ups and other exercises that built up my chest, but those aren't the best muscles for golf, I decided. So I stopped my exercises for awhile. Now I'm doing things that build up my arms and shoulders and legs.”

The more golf tournaments he won, the more caught between worlds he began to feel, particularly as the politics of his homeland began to become impossible for the rest of the world to ignore. After years of being asked how he felt about his South African heritage, Player tried to offer the final word in his autobiography.

“I am an African. My land is the land of the Niger and Nile, the Limpopo and Zambesi, the Sahara and the Kalahari, of the Atlas and Drakensberg and Kilimanjaro. … An immense continent, a prodigious land mass, abundant game, thick with rainforests, barren with deserts, white with rushing waters, populated by millions of people as diverse as can be. In strange moments, I have a revelation of the whole thing, the immensity of Africa, laid out in my mind’s eye as though in one compassing glance; I seem to see the whole long history of the continent not so much enfolding as unfolded, in one piece, in my consciousness — all the native tribes from north to south, all the invaders from the Romans and the Greeks down to the French and the Spanish, the Portuguese and Italians, the Dutch and English, all bringing civilization and devastation with them — and I have a very powerful sensation it is all part of me, and that I am African just as Kikuyu or a Zulu or a Bushman or a Tuareg or a Nubian is African. … History and the collective thinkings and habits of a people over the years influence a man as much as physical environment, and I am influenced by all these things. This is my land. I am South African. And I must say now, and clearly, that I am of the South Africa of Verwoerd and apartheid.”

When you examine Gary Player’s past — all of it — it inspires an interesting ethical question: Should a man should get credit for evolving with the times, or, was his gradual transformation little more than wallpaper meant to cover up the worst of his sins?

In Grand Slam Golf, his 1966 autobiography, Player did not hide his feelings about segregation. In his home country, he supported it unequivocally. The second chapter of the book, in fact, is devoted entirely to the topic, and much of the time is spent pointing a finger back at the rest of the world for sitting in judgment of South Africans.

He writes: “The Americans, the Russians, the British, the French and the Chinese have the atom bomb. These people, all of them, without the slightest of doubt, have the power to destroy all the living world simply by throwing a few switches, and yet these are the people who are the loudest in their criticisms of us and our colour problems.”

The Civil Rights movement in America, Player believed, had little correlation to what was happening in his homeland.

In the book, he writes: “The American Negro is sophisticated and politically conscious,”. “He was ‘Imported’ into the United States and has long lost contact with Africa. He has become an integral part of a western community, with its habits and attitudes. The African is still tribal in his attitudes, owing his allegiance to the tribe rather than a country, and in South Africa alone there must be a dozen different tribes each with separate languages, customs and tribal system. The African may well believe in witchcraft and primitive magic, practice ritual murder and polygamy; his wealth is in cattle. More money and he will have no sense of parental or individual responsibility, no understanding of reverence for life or the human soul which is the basis of Christian and other civilized societies.”

The criticism lobbed South Africa’s way for proceeding slowly toward a more equal society made Player’s blood boil. Besides, he wrote in 1966, segregation exists around the world in many forms. Millionaires, he wrote, don’t mix with postmen, and that is wrong. Maybe the millionaire’s loss. But it is a fact of life.

He writes: “We do not believe that everything can be done overnight — and of course everything that can be done and is being done has to be paid for by the white man. I have no evidence that I live in a police state, a ‘Hitler state’ and the people who write these things and read and believe them, are doing a disservice to the progress of people everywhere. … We in South Africa believe that our races should develop separately, but in parallel.”

When Gary Player wrote those words, Nelson Mandela had already been in prison for three years. He would spend another 24 years behind bars before he was released.

In 1966, a year after Player won the U.S. Open and became just the third golfer in history to win the career Grand Slam, the South African government got its soccer federation re-suspended by FIFA when they proposed — in the name of racial harmony — sending an all-white team to compete in the World Cup in England, then an all-black team to compete in Mexico in 1970.

At the time, Player wrote: “I do believe that the South African government of the day is doing more for the native than any other government we have ever had. I just wish the people who criticize my country would make a little effort to understand it more fully, because I am proud of it. It is my country. It is where I live, and where I shall always live.”

Americans initially did not know what to make of Player, frequently a foil to Nicklaus and Palmer, but he worked hard in an attempt to win them over. When he won the U.S. Open in 1965, he donated his entire purse — $25,000 — back to the USGA, asking that it be used to support Junior Golf.

As he said to the media after the victory: “The American people have been so kind to me since I first came over here, that I feel it is my duty to do something.”

There are dozens of stories like that throughout Player’s history, like the time he paid for 20 orphans to vacation on his farm for 10 days, or the millions he eventually gave to charity.

It did not, however, win the hearts and minds of everyone. At the 1969 PGA Championship in Dayton, Ohio, a group of anti-apartheid protesters interrupted play during the third round, heckling Player and Nicklaus as they reached the 10th green. Years later, recounting what took place, Player and Nicklaus described the events with the same intensity as if they had come under attack during tour in Vietnam.

“They threw telephone books at my back twice,” Player said. “They threw ice in my eyes several times, they charged Jack and I on the green on No. 10 as I was getting ready to hole an important putt, and the ball is between my legs and they screamed in my backswing.”

He tried to return to the state of zen he’d taught himself as a young man, back when he did tai chi in front of a mirror.

“I just tried to adjust with my mind,” Player said. “I met people and I said, "If you want to kill me, you don't have to threaten me. I'll come to your office tomorrow and you can kill me. I'm not going to go home because I don't have a guilty conscience.”

In Nicklaus’ recollection of that PGA, he was prepared to commit manslaughter in defense of his competitor and friend.

“I remember one fella who was probably about 6‑4, 250, charged on the green and coming at me,” Nicklaus said. “I had my putter in my hand and I swear, I would have killed the guy, because I had my putter — I didn’t know what he was going to do. I reared back like this to hit him because I would have and he swerved off, saved his life, saved me and everything else.”

Dan Jenkins, writing for Sports Illustrated, took a slightly different view: As disturbances go these days it was strictly minor league and totally inept. You could have found a better protest in a number of Dayton restaurants when the check came.

"But everybody said boy, they've done it now, those shaggy-haired pigs. It wasn't so bad when they just shot people, burned down cities and tore up universities. Now the lazy, dope-crazed, oversexed, Communist, Nazi, welfare medicare, hippie treasonous Red Chinese spies have picked on golf."

It was not what anyone particularly wanted to have happen in a championship, of course, since Player and Nicklaus were at the time trying very hard to catch Raymond Floyd. But then again, anyone who had ever played much golf on a municipal course would have known that these were normal hazards.

Player, who finished a stroke behind Floyd, took a less humorous view. “I definitely would have won that PGA Championship,” Player said. “There’s not even a doubt.”

For years, he stewed over the protests, and the implication he was a propagandist for the apartheid regime.

In 1978, he told the New York Times: “I really don't understand how you can say that you must penalize an athlete for the policies of his country's government. I mean, what would Americans have said if somebody had suggested keeping Jack or Arnold out of the British Open because of the war in Vietnam? Besides, if you're going to talk human rights, why stop at South Africa? What about the Russians, the Cubans, some of the black countries in Africa?”

In Player’s telling, he was in fact, a critic of Apartheid behind the scenes. He claims to have called for Mandela to be released from prison in the early 1960s, although the evidence of such a claim is difficult to find. Player did, however, go to South African Prime Minister B.J. Vorster in 1969 with the hopes of persuading him to end Apartheid in sport. Player wanted to invite Lee Elder, the first black man to play in the Masters, to compete in the South African PGA Championship. By his account, he was shaking in his shoes when he made the request. But to his surprise, Vorster — a vehement supporter of segregation — eventually agreed.

“I was called a traitor,” Player told the magazine C-Suite Quarterly in 2016. “In those days, you could get 90 days in jail for even suggesting it. Luckily I played some golf with [Vorster]. And I was criticized for doing so.”

The criticism included death threats, although he kept them quiet for years. Player was so scared while traveling abroad, when heard noises in the hotel hallway, he would hide behind his bed.

Lee Elder, reluctant at first, took Player up on his offer in 1971, but only on the condition that black spectators be allowed to watch him play alongside whites. Player had convinced him his views on apartheid had changed as he traveled the world. A friendship began to bloom. 50 years later, when Elder was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame, Player was the man he selected to introduce him.

Elder told the San Diego Tribune in 2021. “I love Gary very much. There’s not a segregated bone in that man’s body.”

As the years went on, Player says he realized that neutrality was not a position he could live with. He came to believe he’d been brainwashed into supporting a quote “cancerous system.”

Player told the Independent in 1996: “The injustice was so obvious and the implications quite chilling. I am now quite convinced that I have played a significant role in trying to eradicate apartheid.”

Subscribe to No Laying Up Emails

If you enjoy NLU content, you'll enjoy NLU emails. We send our newsletter twice a month, and we send a Weekly Digest email. Get monthly deals, exclusive content, and regular updates on all things No Laying Up #GetInvolved

"It's Impossible"

He continued to win golf tournaments at a remarkable pace, including two majors in 1974. His swing was so dialed that season, he stopped shaking hands with friends.

“I feel I've got tremendous power within myself now,” Player said. “I don't want to shake hands too often because I don't want to transmit my power to someone else."

But controversy still had a way of finding him. At the Open Championship at Lytham that year, he produced one of the great performances of his career, grabbing a first-round lead that he never relinquished. His caddie, Rabbit Dyer, also became a star that week as the first black caddie in the history of the Open Championship.

Rabbit told the press that week: "My man complains a lot. I just stick some paper in my ears, and say, 'Don't gimme no jive, baby,' and I make him laugh, loosen him up."

But on the 17th hole of his final round, while leading the tournament by six strokes, Player fanned his approach into knee high grass near the green. A nervous search for the ball commenced. Seconds before Player’s five minutes was about to expire, Dyer found the ball.

Player was able to salvage a bogey, and limped to victory with another bogey on 18 after he had to play a shot left-handed when his approach nestled against the brick clubhouse.

No one ever publicly accused him of anything underhanded, but for years there were whispers, most of them implying Dyer must have dropped a second ball for Player to find in the nick of time.

Years later, addressing the rumors for the first time, Player said: "There are certain things that are possible and certain things that are impossible. First of all they had the TV cameras on during the whole incident. For anybody to say that Rabbit dropped a ball is dreaming. I would put my life on the fact that he wouldn't do something like that. It's impossible. The grass was so thick."

That he never felt as venerated by the fans or the press as Nicklaus or Palmer clearly bugged Player, especially in the twilight of his career. No matter how many tournaments he won, or how much he achieved, he always found himself feeling like the third fiddle in the Big Three. That feeling would follow him for the rest of his career, and you could argue it lingers even today.

In the 1978 Masters, Gary Player entered the final round tied for 10th place, seven shots behind the leader. What unfolded was one of the greatest comebacks in Masters history. The 42-year-old Player shot a sizzling 64, birding seven of the last ten holes to win his ninth and final major. It remains, to this day, the lowest final round fired by a winner at Augusta. Player credited a new putting technique suggested by his wife as the catalyst for his victory.

“I’ve always been a jabber,” Player said. “I knew everyone says the firm wrist stroke is better and all these young guys have been putting so well with it that I finally decided to do as my wife suggested and try it.”

But when he spoke to the press after the green jacket ceremony, Player seemed as interested in settling scores as he did reliving his triumph.

“Last week at Greensboro, I was called a fading star,” Player sneered. “People kept asking me why I haven’t won anything in three years. Why, I’ve been winning all over the world. I won my last three tournaments last year. This is a sore point to me. They do play golf in other places besides America.”

He was, it turned out, just getting warmed up.

“I make five round trips a year between South Africa and here,” Player said. “That’s 8,000 miles a trip. I’d like to see Jack Nicklaus travel like that to South Africa and see how he did.”

He wasn’t criticizing Nicklaus, he clarified. He loved Jack Nicklaus. You could argue that no one loved Jack more than Gary Player. Once, when Nicklaus was traveling to South Africa to play a series of exhibition matches, Player spent $3,000 to increase the size of a lake on his property and stocked it with $1,500 worth of trout so that Nicklaus, an avid fisherman, might better appreciate his homeland.

But Player had been a global ambassador for the game in ways no one else had.

“I have the greatest golfing record in the world,” Player said. “The world, not the United States.”

Player also couldn’t resist taking a swipe at golf course architect Robert Trent Jones, who had been quoted saying that Player’s exercise routine wasn’t good for golfers, that it would quote “tie you up” and rob you of necessary flexibility.

“You do have the last laugh, you know.” Player said. “Tie you up? Crap! Well, Trent Jones’ courses are all tied up. That’s what I think of them. Here is a guy with a stomach out to HERE and he’s talking about physical fitness. I was 150 pounds when I was 16 years of age and I’m 150 today. The night before I won the U.S. Open in 1965, I squatted 350 pounds! I think if a man stays fit, he can play as well at 50 as he did at 30. Nobody has ever done it, but I plan on doing it!”

Player never won another major after 1978, although he also never truly faded from the spotlight, which to him was its own reward. In a lot of ways, it overshadowed just how great he was at golf, how driven he was for more than 50 years. He won 165 times around the world, in countries big and small.

I could spend another hour on all the fascinating, controversial twists that unfolded in the second half of his life — like the time Tom Watson accused him of cheating in the Skins Game; or his genuine friendship with Mandela, whose feet he really did kiss when he met him; or the time he sued his own son, Marc, and grandson, Damian, for selling his golf memorabilia; or the time his other son, Wayne, was banned for life from Augusta National for hawking golf balls during a first tee ceremony for Lee Elder; or the time he was accused of breaking U.S. sanctions by designing a golf course in Burma for the military junta – by the way, he designed over 300 golf courses –; or even the time he said everyone joining the LIV Tour was doing it because they were broke and needed money; or the time he was awarded the Medal of Freedom on Jan. 7, 2021 from President Donald Trump — but it is his press conference after the 1978 Masters that I think captures him at his pugnacious best.

The night before he shot 64 to win the Masters at age of 42, he wanted everyone to know, he had been up until midnight exercising. He was going to celebrate winning his third green jacket, the oldest man to date to ever win one, but he did not intend to rest. Audio of the press conference no longer exists, but if I close my eyes, I can hear his defiant voice in my mind as clear as anything.

“I swear to you, even though I just won the Masters, I will exercise tonight. I never miss my exercises.”

Anything else, in his mind, would have been a tragedy.

———

Thanks for listening/reading.

Many of the anecdotes for this podcast came directly from Gary Player’s autobiography, Grand Slam Golf, which was published in 1966, but is now out of print. The archives of Sports Illustrated and Golf Digest were also essential for research, as well as the stories from the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Independent, ESPN.com, Golf.com and the Associated Press.

Sound editing and mixing for this podcast was done by Justine Piehowski. Story editing by D.J. Piehowski.

If you enjoyed The Tall Tales of Gary Player, you can find more writing like this on our website, which is free to everyone. But we’d also encourage you to join The Nest, our community of avid golfers. Nest Members get a 15 percent discount in our pro shop, access to exclusive content like our monthly nest podcast, as well as the chance to sign up early for our Roost events held all around the country. We appreciate your support.

If you’d like to leave a comment about this podcast, or ask that I never do another Gary Player impression again, you can reach me at kvv@nolayingup.com.

Cheers.

Join The Nest

Established in 2019, The Nest is NLU's growing community of avid golfers. Membership is only $90 a year and includes 15% off at the Pro Shop, exclusive content like a monthly Nest Member podcast and other behind-the-scenes videos, early access to events, and more newsletter-exclusive written content from the team when you join The Nest.