Amari Avery wasn’t afraid. The moment didn’t feel too big for her.

It didn’t matter that she was just a freshman, or that she’d never played in a Curtis Cup. She didn’t flinch at the daunting setup at Merion East.

Instead, she tore it apart.

For two days at the 2022 Curtis Cup, Amari hit booming drives, towering irons, and rolled in almost every important putt. When her opponents chose conservative targets, Amari doubled down and got aggressive.

“I don't see a point in being too calm,” she told reporters, when asked if her style of play could hold up. “I think you might as well get turnt.”

The Curtis Cup — a biennial competition featuring three days of match-play between amateurs from the United States and amateurs from Great Britain & Ireland — has always been a good window into who might emerge as a future star in the world of women’s golf. Amari had been semi-famous in golf circles since 2013, when she was featured as an 8-year-old prodigy in the Netflix documentary “The Short Game” but this felt like the culmination of something that had been building for years.

Her intimidating glare and her fluid, athletic swing was the buzz of the competition.

It felt like an arrival.

She was so good, the United States couldn’t take her out of the line-up. She went 4-0 over the first two days, and when Amari walked into the press tent at Merion on Saturday night, the prospect of a perfect Curtis Cup immediately came up. It was something only three players (Stacey Lewis, 2008; Bronte Law, 2016; Kristin Gillman, 2018) had accomplished. Was Amari about to be the fourth?

“You could not have dreamed this, right?” a media official asked.

A sense of eagerness and hope dawned on her.

“No, I could not have put it together like this,” Amari said.

Later that night, something about the chase for perfection began to haunt her. It wouldn’t go away. The United States had a commanding lead, but she couldn’t shake the feeling that she had to go 5-0. Someone brought it up minutes before she teed off for Sunday singles. It lingered. She was in the anchor spot in the line-up, teeing off last, in case the United States needed a hero late.

Matched up against GB&I’s Emily Price, who’d struggled to win anything all week, the thought of a sweep bothered her more than her opponent. She missed her lines. Her drives found the rough. Though the United States won the Curtis Cup long before her contributions mattered, Amari was the only player to lose a match all day, falling 4&3.

When the matches ended, there was an eruption of red, white and blue. It was one of the most decisive wins in the competition’s history, with the U.S. prevailing 15 ½ - 4 ½. As they gathered greenside, players hugged and high-fived. They draped one another in American flags. Amari participated and was elated for her teammates, but watching perfection slip through her fingers continued to eat away at her joy.

After several minutes, she could no longer fake a smile. She waited for a quiet moment to escape the noise and slipped into the Merion clubhouse.

Finally, alone, she dissolved into tears.

“I was heartbroken,” she said, reflecting a year later. “I wanted to make history. I'd been playing so well.”

At the Augusta National Women’s Amateur this week, Amari will be back in the spotlight once again. Her aggressive, athletic brand of golf will be put to the test as she tries to capture arguably the most coveted title in the women’s amateur game.

But Amari — now 20 years old — is no longer chasing perfection.

She had to learn to redraw the blueprint for her own success. Moving forward meant knowing and accepting that her best would need to be enough.

It just didn’t happen overnight. She needed time and space and independence.

She needed to discover the real Amari Avery.

Imagine you’re 8 years old, at a point in your life where your feelings, goals and relationships are barely realized. You love golf, and you love your dad, but your emotions are still developing. Then someone thrusts cameras in your face for your most vulnerable moments. For a decade, even after you’ve left that kid behind, that narrowly illustrated picture is who people assumed you were.

Would it feel like you were trapped in a portrait you didn’t even draw?

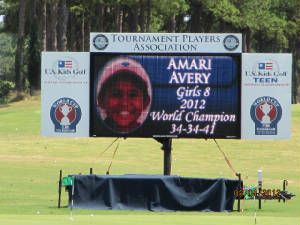

“The Short Game,” released in 2013, offered an intimate look at the lives of five promising junior golfers and their families as they spend six months preparing to compete in the U.S. Kids Championship at Pinehurst. This was the world’s introduction to Amari Avery – often remembered as the most polarizing depiction of the entire documentary, which featured sequences of Amari — referred to in the film as “Tigeress” — having heated moments with her father, Andre.

Even in her continued ascent as one of the greatest players in the world, that has been the stamp on Amari's golfing existence. Her father’s too. They didn’t have a map of how to get there, so they did their best. He caddied every round of hers that he could and tried to help with her swing.

It wasn’t always pretty. But her potential seemed immeasurable.

“Ever since she was six years old, I can recall many times when parents would ask me, ‘How is she hitting it so far? What are you doing?’ Nothing,” Andre said. “Some people just have it – some people just don't. We just want to control it.”

Her temper was as explosive as her drives. So was Andre’s. For a long time, it felt like they were on trial for having normal human emotions. It’s a legacy that she’s wrestled with for years.

“I think there's a lot more to me than just those two things,” Amari said. “And they made up a big, huge part of my life. But I think that moving forward, the second chapter of my golfing career, I think that needs to kind of change a little bit. People should focus more on my golf instead of the things that have happened in the past.”

A Curtis Cup, a near NCAA Championship, five collegiate wins, competing in major championships, rewriting record books – all these things are often absent when her name appears in a headline. She’s been fighting tooth and nail to tell the story of who she truly is, and yet her legacy feels chained to a characterization she’s struggled to escape.

The little girl, who once seethed after bad shots and fought back tears after bogeys, grew up. She’s a woman now.

It’s time for her to reintroduce herself.

Amari's teenage years mimicked the ritualistic nature of her childhood – and neglected the coming-of-age rewards: No field trips, homecoming dances or prom. That was the trade-off for a golf community, for cross-country travel and entry into rooms in clubhouses normal kids weren’t allowed to occupy.

It was plenty fulfilling. The trophies stacked up so high, they felt like giants, and so did the college coaches who were lining the fairways when she was 12 – one of the best years of her entire junior golf career.

But the following year, something felt off. The wins began to vanish, and so did the coaches. It was the first sustained slump of her career, and it felt like her world was unraveling.

What if no one believed in her?

One assistant coach, from a school not so far down the road, went against the grain. He started coming around even more. Justin Silverstein never wavered. He wanted her to be part of the USC program.

“Justin just happened to be there all the time,” Amari said. “He was at every event: Small qualifiers, big tournaments. That felt special to me. (I realized) no matter how I play, he knows what I can bring to the table. That’s what I want in a head coach.”

The slump faded, but the allure of USC remained. If she was going to attend college, she was going to be a Trojan. But well into her junior golf career, the recruitment process remained one large audition. The Avery family wasn’t entirely sure if their daughter should head to college or turn professional when she turned 18. Again, who had a blueprint? Lexi Thompson and Nelly Korda had skipped college and found success, while Lilia Vu and Jennifer Kupcho benefitted from remaining amateurs.

When Amari was 15, Andre enlisted the help of Sean Foley — who has worked with Tiger Woods, Lydia Ko and Justin Rose, among others — to teach both Amari and her younger sister, Alona. The ask? Nothing significant. Just a refinement of the core parts of what already made her stand out: A graceful, speedy tempo that leveraged all the power she could physically muster.

Foley understood the assignment immediately.

“That’s like someone that’s brought you a Lamborghini that has been sitting in the garage for six months and it really simply needs to be cleaned, have the oil changed – because the overall car is unbelievable,” Foley said. “You couldn’t even build a car that good. That’s her natural gift of athleticism and physical ability.”

Having watched countless range sessions and Amari’s dominance in real-time, Silverstein was well aware of all that. He knew that Amari raising her bar meant he had to bring his best sales pitch, too. A promotion to head coach helped – but the end of her high school career occurring during lockdown meant that would have to be delivered over Zoom.

It could have been perceived as a losing battle. The opportunity to make money on either the LPGA Tour or Epson Tour would begin on her 18th birthday. Was it worth delaying her potential brilliance?

Subscribe to No Laying Up Emails

If you enjoy NLU content, you'll enjoy NLU emails. We send our newsletter twice a month, and we send a Weekly Digest email. Get monthly deals, exclusive content, and regular updates on all things No Laying Up #GetInvolved

With pending NIL legislation a possibility, that answer was turning into a maybe. Amari's Netflix fame, once a burden, suddenly had a potential upside.

That option looked even better when Silverstein made it clear he was open to bringing Amari in regardless of how short her USC career could be. His promise to the Avery family? He would make her as good as she could be, even if that meant she left in just six months. Staying close to home, where she could visit on the weekends and still watch her younger sister grow up was also comforting.

Still, there was some pause. College golf, while responsible for many success stories, has no guarantees. And Andre, her liferaft during every bad round, would have to give up being her full-time caddie.

“I thought we should try to hold on to our kids and keep them around,” Andre said. “But there’s the point where you have to let them find out who they are.”

Her objective at USC was simple: Get in, get better at golf, and get out.

Maybe I’ll meet some friends, she thought to herself. But besides that, it’s just golf until I can turn pro.

She wasn’t the biggest fan of school, to be honest. It was just a means to an end. She’s been homeschooled most of her life, which felt necessary with all her travel, but she saw homework and tests as little more than an obstacle. She’d get them done, get outside, and then the real education — her golf — would follow.

How hard could sitting in a college lecture hall be? Surely not as hard as beating people on the golf course. Right?

Tell that to a freshman Amari, who sobbed to her roommate/teammate Brianna Navarrosa the night before Amari’s first day of class in early 2022. She only understood what one-half of being a student-athlete required, what most would consider the hard part. It’d been so long since she had been in any kind of classroom, she was riddled with questions and anxiety.

Do I dress up? Do I bring a notebook? How do I take notes?

In enrolling early at USC, she’d left behind her sister and best friend, Alona. But a sisterhood among her teammates started to take shape. The next day, another teammate, Christine Wang, walked her to the designated building of her first college lecture. Soon she was spending hours a day with her teammates in practice, workouts, attending football games, doing homework, watching (and occasionally producing) a series of TikToks.

“I’m proud that I created a life outside of golf for myself,” she said.

The golf part was even easier. Amari would break out immediately, winning three events in her first semester and finishing almost exclusively in top 10 in others. She quickly catapulted to the top of the college golf world, which included her playing her second and most successful Augusta National Women’s Amateur, tying for fourth.

But that pesky thing called “school” lingered. Five to six hours a day of golf practice wasn’t sustainable if she wanted to remain a student-athlete at USC. Her grades began to reflect that effort.

Everyone involved knew the deal: Amari’s future at USC was under constant evaluation. But with her first semester being the struggle it was, she was going to have to seek a greater level of balance in order to stay.

For the first time in her life, golf was going to have to take a backseat.

She managed to win one event in her second semester, but wouldn’t see another individual win again in her sophomore year. The following spring, at her third Augusta National Women’s Amateur, she was candid about her struggles.

“I don’t expect to match what I did my first spring. That was magical,” she said. “I feel like I’ve been playing similar – just haven’t been putting up the scores lately. But I think it’s a mental challenge at this point, kind of going through and figuring it out.”

In tournaments, she kept fighting to unlock any ounce of that early dominance. But she wasn’t the same. Extra hours to make up for how school went in the first semester and adjusting to living quarters off campus would bring out a fairly uncharacteristic side of Amari.

“I found myself making excuses,” she says. “They want you to show up in both – there’s a standard for school and golf.”

The NIL responsibilities had also started lining up. She had a deal with Nike, a deal to use TaylorMade clubs, and she appeared in a Bank of America commercial. Later that summer, she’d even partner with Lexus.

She maintains the game was always there, which was true. Amid her slump, USC was on an incredible trajectory. The Trojans went from just one team victory all season to capturing the 2023 PAC-12 Championship and going on an unprecedented run to the NCAA Championship title match. USC would knock out Stanford 3-1 in the semifinals before taking on Wake Forest, where Amari would lose to Curtis Cup teammate and Wake Forest star Rachel Kuehn.

Amari's greatest takeaway from that run had nothing to do with their victories. It was the words of a wise teammate, Cindy Kou, who suggested the team do a “winners” chant after advancing to the semifinals.

Some of the Trojans objected. It was premature. The job wasn’t done.

“You don’t have to win to be a winner,” Kou said.

The athletics department at the University of Southern California can feel, at times, like the backlot of a Hollywood studio. Everywhere you look, there is someone famous. There are Heisman winners. Olympics gold medalists. Future All-Pros. You might even catch a glimpse of Bronny James and his famous father. There are ball players who shatter backboards and female athletes who shatter glass ceilings, all around.

It can make for fascinating social experiments for their peers, the normies who sit in classrooms beside them. In theory, there is no difference between the names next to each other on an enrollment sheet, but NIL has widened the reality. Student-athletes sit next to peers who already have an abundance of fame and riches. It can create an awkward dynamic if you let it.

In a recent lecture, Christine Wang — Amari's Trojan teammate — was listening to a guest speaker from the athletics department give a talk about trailblazers in college sports. The speaker used local, contemporary examples: 2022 Heisman winner Caleb Wiliams and freshman women’s basketball superstar JuJu Watkins.

Something bothered Wang. Why wasn’t the lecturer mentioning her teammate, Amari – an equally accomplished athlete? Because she plays golf?

Seconds away from raising her hand, the lecturer moved on. Wang later pulled out her phone, knowing Amari would have the same class later that week: “You got to say something. You deserve to be on that list. I don’t see a difference between you, Caleb Williams, and JuJu, other than what you play.”

Amari was grateful but hungry for more.

2023 wasn’t a Curtis Cup year, but she had other USGA honors to chase. She qualified for the U.S. Women’s Open at Pebble Beach, a dream come true of a venue. For the first time, the course was hosting a championship for women. Who knows the next time a chance like this might come along? After thinking deeply about it, Amari decided there was one person who needed to be there, on her bag, to share the experience.

Her dad, Andre.

Andre knows, these days, that he did the best he could with the knowledge he had. The lessons he learned from caddying and parenting Amari were handed down to Alona. Raising a pair of golf-obsessed daughters who want to be the best players in the world hasn’t been easy, but they’ve learned lessons from each other. Amari, he says, now navigates her golf with a calmer, level-headed temperament. She might need a reminder or two before something completely sets in, but she will get it, he says. And though most of younger sister Alona’s visibility has been on the sidelines as Amari’s biggest fan, her own promising golf career (she’s signed with UC-Irvine) has been navigated with her own tangible ferocity and skills.

Like the athletic greats he tried to model his older daughter’s success off of — Tiger Woods, Venus and Serena Williams — he realized there was a level of growth and accountability that had to take place on both sides to evolve.

“You have to grow with the child,” he says. “As she grew, I grew. There’s no need to yell and curse and scream. We sit down, we talk and we try to navigate things through communication.”

Navigating their world with compassion and understanding allowed the Averys to grow closer than ever before – and more unified in their goals, too. Andre might have altered his approach, but his commitment to taking his daughters to the top has never wavered. When he talks about his recent caddying gigs with his daughter, his words are laced with a whiff of nostalgia, recalling moments unique to her on-course habits. He knows there aren't many of these gigs left. But his belief in his daughter’s potential is more reminiscent of a loving father than a demanding one.

At the U.S. Open, Amari was in the middle of a lull with her ball striking, but her athleticism was still jaw-dropping. A first-round 70 where she tied for 3rd immediately put her name in the low amateur conversation, and while she faded over the weekend as the wind picked up, she led the field in driving distance, averaging 273.2 yards, and finished third in strokes gained off the tee.

There were still hints that the Averys’ Netflix fame may follow them around forever.

A sizable crowd came out to watch Amari during her opening round, and they’d stay with her throughout the weekend. One round, the crowd swelled as the Averys made the turn. On the 16th tee, the murmur was so loud, and the spectators so thick, they were too tough to tune out. When Amari smashed her drive, she couldn’t wait to walk down the fairway just to get some space.

“I don’t think I like that,” she said to her dad.

“Like what?” Andre asked, puzzled.

“I don’t like how they yell – like they’re right up on you, and they just yell,” she said.

Amateurs play in front of calmer galleries, if they have galleries at all. This was a new world.

“Well, you’re going to have that for the rest of your life,” Andre responded. “You might want to get prepared for that.”

The dream of turning professional feels closer now than it ever has.

Things are clicking at the right time for Amari. Once eager to leave amateur golf behind, she now feels like her time at USC has been invaluable. Silverstein calculated that by the fall semester in 2023, Amari had picked up a shot and a half in strokes gained on the greens since her freshman year.

“It’s six shots in an LPGA tournament,” he emphasizes. He attributes that improvement to speed control.

Harnessing her power over the ball was a large area of focus, too. A lot of college golfers enter programs lacking course management skills, but almost all of them lack the distance and power Amari brings to the table. Her yardage control saw some strides immediately – but in her final year of college golf, her ball striking has come into focus. “We want to send her out of here hitting it better than she ever has,” Silverstein says.

It was a good time to use Q-School as a litmus test, entering for the first time in late 2023. She finished in the top 20 at Stage I and advanced to Stage II, where she’d fail to qualify for Q-Series – but left with a little bit of Epson Tour status. She was content with that, she says. LPGA status would have meant she’d be forced to wait to play that following spring, time she preferred to spend at USC.

“It just makes me a little nervous. Because I don't know what's coming yet,” Amari says. “I have a plan of what I want my life to look like in the next year or so. But I do know that it's gonna be a huge shift compared to where I'm at right now.”

The extra college reps have been meaningful. At the Juli Inkster Meadow Club Invitational in early March, USC’s second stop of the spring semester and Amari's last event before her final Augusta National Women’s Amateur, Amari once again mesmerized the field with her two greatest weapons: Her driver and wedge.

During a pre-tournament practice round, Amari's teammates Catherine Park and Bailey Shoemaker — two amateur stars in their own right — couldn’t resist consulting Amari on each tee box for strategy. Most of the time, Amari had an answer. Other times, she poked a little fun at herself.

“Every time I play this hole,” she said, looking down the fairway of the par-5 13th, “Fade, draw – it lands in the left bunker.”

That might be helpful advice if everyone could hit it as far as Amari. Still, they heed her lecture and find the fairway. Thankfully, the practice round isn’t all business – there’s plenty of goofing around and lighthearted banter. It feels like even on this cold, rainy March day – unlike the ones spent in Southern California – their laughter made the trip with them.

“I think we’re the only team having fun,” Amari said, looking around.

Shoemaker corrects her: “I think we’re just delusional.”

The group erupts in laughter.

Amari knows these treasured moments are numbered. When the competition rolls around the next day, she greets her playing partners, Kajsa Arwefjall and Paula Martin Sampedro, who she’ll also see at the ANWA, but she’s quickly annoyed with her own game after her opening tee shot finds the right rough. She calmly gets back on track after returning to the fairway, pitches it to the green and makes a five-foot birdie.

The rest of the front nine illustrates a pin hunter on the prowl. At this point in her career, power is her language, and she speaks it fluently, playing a game that feels unfamiliar to the rest of the players in the field. Her drives come to rest 40-50 yards ahead of her competitors. It’s not uncommon to find her waiting on par 5s.

The Lamborghini is humming until she reaches the dogleg left 7th and blasts her three-wood into the side of a hill. She and her playing partners make an attempt to search for her ball, but it rests at a perilous angle. The rules official drives her back to the tee box to hit a provisional. The sequence that follows is far more conservative – she finds the fairway this time, but the eventual double bogey is a blemish on her scorecard.

When Amari catches up with USC assistant coach Tiffany Joh on the tee box of the next hole, she explains the situation. They both laugh it off.

A few years ago, that kind of mistake would have left Amari seething. These days, she has learned to recenter herself and attack the next hole – having recognized the value of forgiving and forgetting. Those traits will be invaluable this week in the ANWA if she climbs into contention.

There is an alternate timeline where Amari could have spent the last two years living out of suitcases, hustling to fulfill sponsor obligations, and trying to survive in the cutthroat world that is professional golf. Instead, she became a fearless young woman who redefined her why. She learned to smile more, to laugh more. She learned that by establishing a routine not centered around golf, she could find liberation. She could even grow closer to her family by getting some space.

The lines of Amari's blueprint are suddenly more visible – and a little more original.

Amari Avery is not running from who she was. That fiery little girl is still with her, but the snapshot the world saw a decade ago no longer defines her. She's evolved into a woman who has learned to laugh at her mistakes. She channels heartache into motivation these days. She's letting herself dream of all the big moments still to come.

Jordan Perez writes about golf for No Laying Up.

Email her at jordan@nolayingup.com.

Join The Nest

Established in 2019, The Nest is NLU's growing community of avid golfers. Membership is only $90 a year and includes 15% off at the Pro Shop, exclusive content like a monthly Nest Member podcast and other behind-the-scenes videos, early access to events, and more newsletter-exclusive written content from the team when you join The Nest.