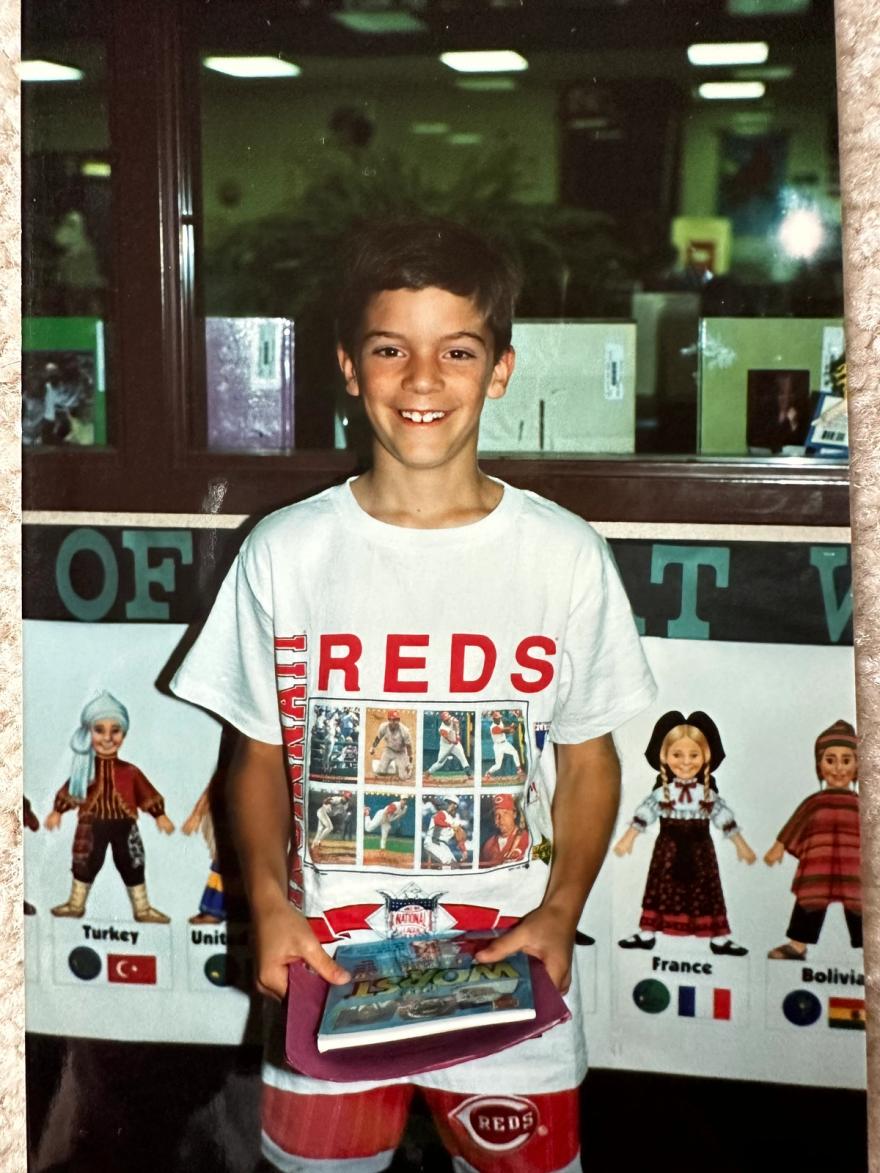

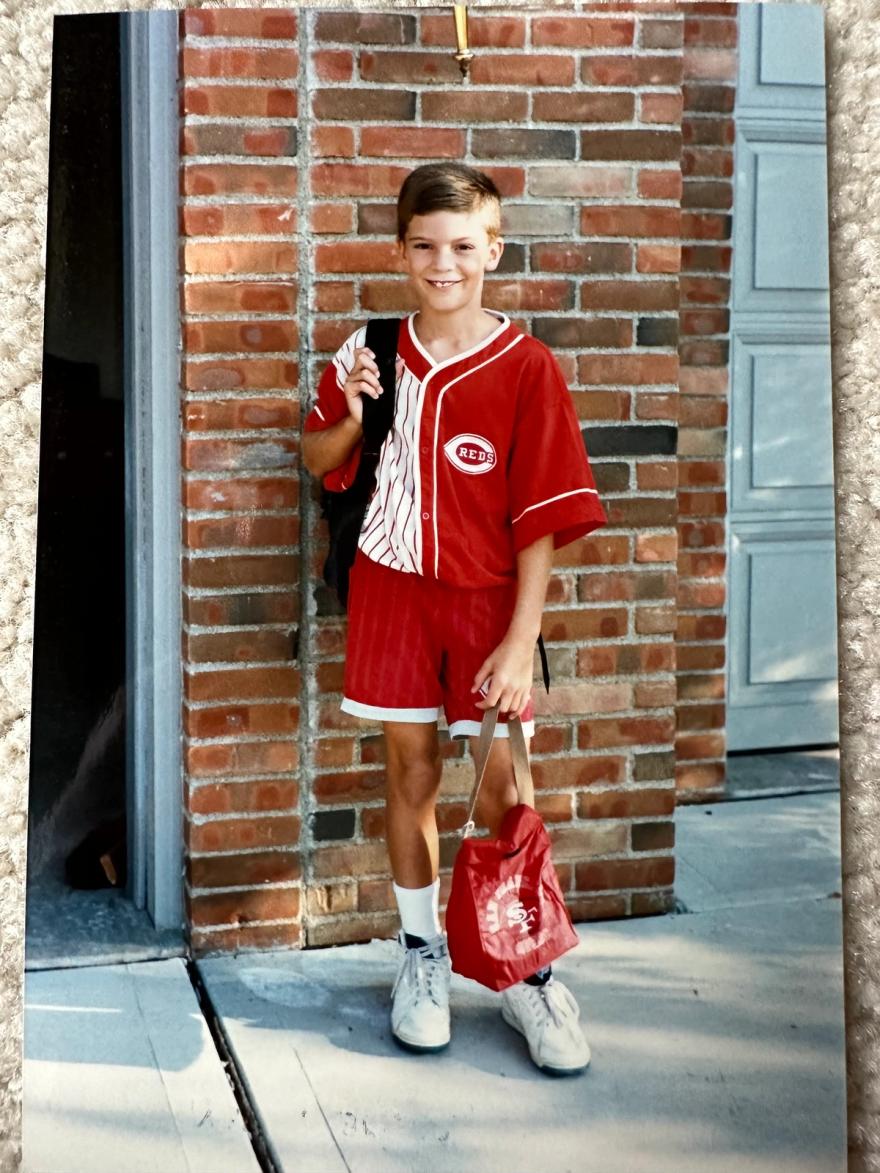

Every summer night when I was a kid, I would sleep on the pull-out couch in our basement. It was cooler down there than up in my room, and there was a little TV where I could watch Baseball Tonight several times over, soaking up highlights (again and again) until I could barely keep my eyes open.

In the morning, I would wake up and play baseball, often by myself. Since I couldn’t pitch to myself, I would hurl a tennis ball against the garage, then get into my crouch and try to hit it over the house and into the backyard. I was a righty hitter, but had to play this game left-handed, because the second story was on the pull side, and I was trying not to break our windows.

I only broke a window once, at least from what I remember. Looking back, our next-door neighbors were ridiculously patient with me as I peppered their house with pulled foul balls.

When I grew tired of hitting, I would fire the tennis ball for hours against the brick pylon between our two garage doors, pretending I was painting the corners of the strike zone. I threw so many imaginary pitches, a wear pattern started to emerge on the brick. It’s decidedly not on the corners of the strike zone and might explain why I spent a fair amount of my high school pitching days craning my neck to watch balls sail over the outfielder’s heads.

That wear pattern still exists to this day at my parents’ house, a permanent reminder of what it felt like to be a kid who loved a sport in ways he couldn't begin to put into words.

I can’t say exactly when Joey Votto became my favorite professional athlete to ever walk the earth, only that it happened the way these things sometimes go, gradually, then suddenly.

He didn’t sneak up on me, necessarily. I saw his name in Baseball America. I read the scouting reports. I understood he might one day be a contributor to the ballclub. But it never crossed my mind that he might be The Dude. If you polled Reds fans in 2005 or 2006, I think 90 percent of us would have told you Jay Bruce was The Prince Who Was Promised. He was the Beaumont Bomber, the generational talent who had the potential to be a savior.

Votto seemed, by comparison, like just about any other prospect. There’s potential there, sure, but is there anything special?

He was a little older than Bruce, and he arrived with considerably less sizzle. A Canadian kid from the suburbs of Toronto, Votto’s approach to hitting in the minors was methodical, whereas Bruce’s was instinctual. Votto had a great ability to avoid making outs, and if he had a strength, it was his patience. Every at-bat was a chess match. Votto, vs. the pitcher. Bruce, by comparison, dominated minor league pitching with pure talent, particularly in 2007, when he was Baseball America’s Minor League Player of the Year.

It was easy to get excited about Bruce, and all the potential wonders soon to unfold. I had not one, but two Jay Bruce jerseys. I even sprung for the authentic one at a time when I absolutely should not have been spending $200 on a jersey, just because I could not stand how cheap the letters and numbers looked on the back of the replica.

It was hard to get excited about a guy with an excellent walk rate.

Baseball, however, was in the midst of what can only be described as a modern enlightenment, a sea change of strategy and thinking. It would take years for it to permeate the public consciousness, but Votto was at the forefront of the idea that the most important skill a hitter could possess was to avoid making outs. Home runs, hits and RBIs still mattered — and he compiled plenty of those traditional stats — but they didn’t matter quite as much as simply getting on base as often as possible.

Counting stats has traditionally ruled the day with baseball fans, but it led us all to very faulty conclusions. To this day, if I surveyed pretty much any audience with the question of who was the better hitter between Joey Votto and Tony Gwynn, the majority would almost certainly choose the wrong guy.

Votto did not give away at-bats.

No matter how bad the Reds were during certain stretches of his career, no matter how far away they were from being competitive, he believed that every time he walked to the plate, the people watching (even if they were Cubs fans!) deserved his best effort.

I could cite a hundred different stats that would paint a picture for you, but here is perhaps my favorite of all: In 8,746 major league at-bats, Votto popped up once to the pitcher.

One time. He was a freak.

When Votto announced his retirement last week at age 40, I was surprised how hard it hit me. It was the end of an era for me, and thousands of Reds fans. But mostly I was grateful. I was grateful he never had an at-bat in the majors for anyone but the Reds, having spent 17 seasons in Cincinnati before one final stint in minors with the Blue Jays. I was grateful he came into my life when he did, and that he drew me back to baseball when I thought I’d left it behind.

I was grateful — in the end — for everything I got to witness.

He was only two years older than me, which seemed hard to believe when I was living through my 20s. Professional athletes never feel like they’re supposed to be your peers, but then one comes along, right as you’re coming of age, and suddenly the ebbs and flows of their career become a touchpoint for certain periods of your own life. If you’re lucky, they become a constant, a reminder of home, even as you live through job promotions and break-ups and celebrations and disappointments.

Votto made his major league debut in 2007, hitting .321 in 84 at-bats, but it wasn’t until 2008 that he grabbed a permanent spot in the Reds line-up. That was the same year I graduated from Miami University and ventured out into the world. I landed a job in Chicago, and I rented an apartment on West Patterson, 180 yards west of the stadium. We were so close that when you watched Cubs games on television from our living room, you could hear the roar of the crowd filter through the windows before the broadcast could catch up, the promise that something exciting was unfolding, somehow outracing your eyes.

I hated the Cubs, but the Reds meant more to me than I can properly put into words. I don’t really know why. They never did anything in my childhood to deserve the love, and through the 2000’s, the franchise was essentially in disarray.

But for some reason, I lived and died with every series, and when they came to town, I had to be at every game. For a weekend series, I might splurge for bleacher seats. But a Monday night game, you could catch me up in the rafters after scalping a $10 ticket in the 3rd inning.

The team was still mediocre, but Votto was already a force by 2009. I took almost a perverse pleasure in watching him torment Cubs fans. He understood his role in the rivalry. He’d trash-talk their fans, particularly kids, in the most playful way possible. He won the MVP in 2010, and he could hit at any ballpark, but his numbers at Wrigley were always especially good (.321 average; .422 OBP; 1.029 OPS) and I can remember sitting in a sea of Cubs fans, night after night, and feeling like: Dude, that’s our guy.

At long last, we’ve finally got a guy.

Being a die-hard fan of a sports team you grew up with — especially when they’re a small market team — isn’t particularly easy. You dedicate so much time and energy and free time to it, hopeful there will be a payoff that makes it all worth it. Votto was one of the few athletes to ever make me feel like every minute of my time spent was worthwhile, and in 2012, it felt like his moment, and the Reds’ moment, had finally arrived.

Their pitching was incredible. The line-up was solid. They had guys under contract, or under control, for several more years. They weren’t big spenders, but a long-term approach to team building had finally paid off. In the middle of the line-up was Votto, our patient magician. His OBP was a ridiculous .474 that year, the best number of his career. In an early-season game against the Nationals, he hit three home runs — including a walk-off grand slam — in a 9-6 Reds win.

They won 97 games that year, won their division, and in the division series, they took a 2-0 lead against the San Francisco Giants. They were returning to Cincinnati for three straight games, needing to win just one to advance.

It was the kind of joy that felt like it wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

The Reds proceed to lose all three games.

When Buster Posey hit a Grand Slam in Game 5 of the series, something fractured inside me. I legitimately think I went into a pit of despair.

You try to be optimistic, you try to tell yourself they’ll have another shot, but deep down, I knew their window was essentially closed.

That was their best chance — Votto’s best chance — and it came and went.

The next few years forced me to reevaluate some things. Votto kept plugging away (he hit .305 in 2013 and led the National League in OBP for the fourth straight season) but something inside me had shifted. I started to question myself: Why did I care so much about something I had no control over that could wound me so deeply?

That’s a bit of a dangerous thread to pull on as a sports fan. There’s no denying that, at my core, I cared deeply. But why? The Cincinnati Reds are the only professional sports franchise I’ve ever actually cared about. But why? They haven’t won a postseason series since I was nine. As a kid, you never had to wrestle with why you cared about the team you’re rooting for. You just did it because you didn’t know any better.

But as an adult, I knew I was wearing the losses more than I should have. I knew a part of me needed to grow up, to stop investing every spare moment I had into the whims of professional athletes. If it wasn’t the Reds, it was an entire Sunday watching NFL RedZone. I needed something different in my life.

When my job offered me a position in Amsterdam, I decided to take it. I stopped following baseball, and pretty much all of American professional sports, almost cold turkey, knowing I could never keep up with the time change. What little free time I had, I’d spent on traveling or on following professional golf, which weirdly was the only sport whose time zone played in my favor. Also, it couldn’t hurt me! (At least that’s what I told myself. Yet the 2016 Masters would have something to say about that.)

I continued to get alerts for the Reds. I checked in on the box scores, the prospect lists, and the potential breakout candidates. But when I returned to the States three years later, I’d occasionally scroll past a baseball game and realize: I don’t actually need this thing.

Votto didn’t need me either, it turned out. He continued to grind, and give his best, even as the franchise began to crumble around him. He hit .326 in 2016 (with .434 OBP) and probably should have won the MVP in 2017 when he hit .320 and had the highest OPS of his career (1.032). The team around him, however, was dreadful. Bad pitching, bad roster building, you name it. In maybe Votto’s best season, they won just 68 games and finished last in their division.

I almost hated myself for thinking it, but a part of me wanted him to get traded. My affinity for Votto had outgrown my affinity for the franchise. He deserved better than this. The fans were furious with ownership, ownership was frustrated with the economic reality of trying to win in a small market, and Votto was like a kid watching his parents at each other’s throats at the end of a bad marriage.

One thing you grow to expect as a fan of a small market team (and a poorly run one at that) is that, when you do have a superstar player, eventually they’re going to want to move on to greener pastures. More money, a better chance at a World Series, and a more enthusiastic fanbase to play in front of. And that’s extremely understandable. The Cincinnati Reds are very far from the best that Major League Baseball has to offer.

Joey Votto was a lot bigger than the Reds, but not once did he ever intimate as such.

Instead of complaining, he showed up at spring training every year and said something absurd: I believe in the ball club. I think we’re going to be great.

They had no chance, absolutely none at all, and yet Votto refused to be anything other than the consummate professional.

Age and injuries eventually began to take their toll. Teams began deploying the shift against him, and his average plummeted. He battled injuries that zapped the majority of his power. 2018 was a disaster for the Reds and for Votto. There was just no hope, it felt like the end was near. I paid very little attention from afar, turned off by the slog that modern baseball had become.

2019 somehow started even worse. The Reds were sitting at 5-12 as they were held to 3 hits on a getaway day in Los Angeles, and the team packed up their stuff onto the busses and rolled out to San Diego.

Everyone, except Votto. Reds reporter C. Trent Rosecrans waited, and waited, and waited for Joey Votto to make his way to the locker room. After 56 minutes, Votto finally appeared, drenched in sweat with red clay on his hands.

“Well, I do feel like I have some technical adjustments to make,” he said. “Listen, I would be honest with you, I’m not ready to concede. It’s just not over. It’s just not over. I’m going to be an entertaining player, an entertaining hitter. It’s not gone. I’m sorry, it’s just not….This isn’t self-rah-rah, I just…

Votto turned to teammate Jesse Winker and asked a question.

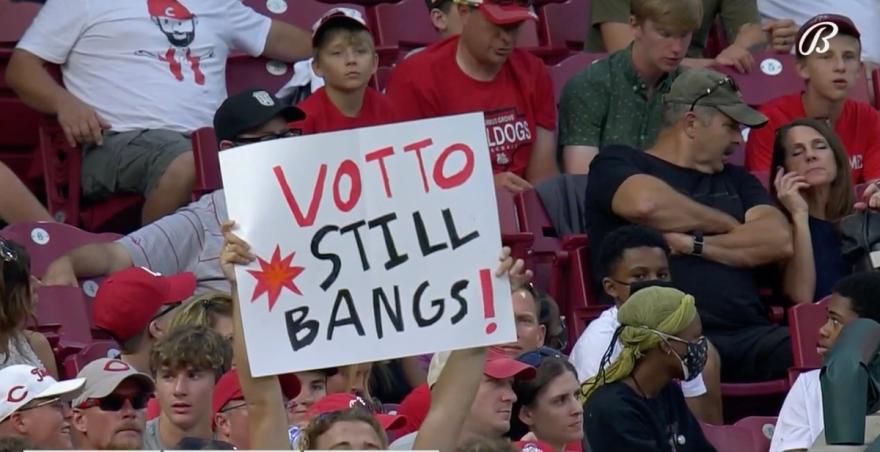

“Jesse, can I still bang?”

“Yes, bro. That’s a terrible question,” Winker replied.

As it turns out, Votto wasn’t just blowing smoke up our asses. Though 2019 was not the success he was hoping for, it was not over.

Votto returned from a choppy 2020 COVID season having reinvented himself as a modern power hitter. His batting stance was different. His swing, and his approach, had been modernized. He started to drive the ball again. He hit a home run in seven straight games at one point and climbed into the MVP discussion. He looked like he was having more fun than he’d had in years. He started goofing around on social media. He dressed up in a Mountie uniform for an interview. He posed like Jamie Tartt from Ted Lasso after he hit home runs.

Reds fans started throwing around a saying that I couldn’t help but feel drawn to. They put it on t-shirts, announcers worked it into their home run calls, and it felt like a declaration, not a question.

Votto still bangs.

His resurgence couldn’t last forever. Father time wore him down, just like it wears me down some days. (He was plagued by a bad shoulder; me with a stiff back.) But even when he was injured, he did whatever he could to entertain Reds fans. He came to the ballpark and roamed around the stands taking photos with his supporters. He’d drop by the TV booth, answer questions, and stay for the entire game. He took improv classes in the offseason to try and become a better entertainer, just for the sake of baseball. He spoke of the fanbase in reverent terms that we probably didn’t deserve.

He made me want to tune in for whatever magic he had left.

In 2023, the Reds called up a young shortstop named Elly De La Cruz. He was nothing like Votto. He could fly on the bases and he swung on pitches outside the strike zone much too often. But there was no denying his electricity.

Baseball had made some long-awaited and much-needed rule changes, implementing a pitch clock and banning the defensive shift, and De La Cruz was appointment viewing. Coming off a 100-loss season in 2022, the Reds had somehow peeled off 8 straight wins by mid-June, all without Votto, who was rehabbing an injury. Votto returned to the lineup on June 19 and sent the first pitch he saw in the 5th inning halfway up the moon deck and sent Great American Ballpark into a frenzy.

He was amped. His much younger teammates donned him with a Viking helmet and a cape, and he emerged gleefully out of the dugout for a curtain call.

A tidal wave of emotions came over me. Votto had waited out losing team after losing team after losing team, and at age 39, he was getting a career curtain call. Hope had returned to Cincinnati.

Votto was the bridge that guided me back to the sport that I loved. He handed me the gift of watching De La Cruz, and in his last gasp, the Reds made one final playoff push. That they fell short almost didn’t matter. Votto’s commitment to his craft and to the team, even in the darkest times, ended on a hopeful note.

I know Votto is a unicorn. I won’t fool myself into thinking De La Cruz will be a Red for the next 15 years. He’s destined for a big-market team, and while that’s disappointing, it’s the reality of rooting for this team. I’ll enjoy him for as long as I can.

Sometimes in sports, you only get one guy you can truly invest in, a guy who you’ll defend in every argument until the end of time. I already have people in my texts this week teasing me that Votto’s not a Hall of Famer, that he didn’t have enough hits or he didn't have enough home runs. They’re wrong, but that still doesn’t matter to me.

Joey Votto made me feel like every second I invested in loving the game — whether it was a broken heart, a broken window, or the wear marks on the bricks of my parents' house — was worth it.

And Votto still bangs.

Chris Solomon is a co-founder of No Laying Up.

Email him at soly@nolayingup.com